Last week, I attended a film festival dedicated to shorts made using generative AI. Dubbed AIFF 2025, it was an event precariously balancing between two different worlds.

The festival was hosted by Runway, a company that produces models and tools for generating images and videos. In panels and press briefings, a curated list of industry professionals made the case for Hollywood to embrace AI tools. In private meetings with industry professionals, I gained a strong sense that there is already a widening philosophical divide within the film and television business.

I also interviewed Runway CEO Cristóbal Valenzuela about the tightrope he walks as he pitches his products to an industry that has deeply divided feelings about what role AI will have in its future.

To unpack all this, it makes sense to start with the films, partly because the film that was chosen as the festival’s top prize winner says a lot about the issues at hand.

A festival of oddities and profundities

Since this was the first time the festival has been open to the public, the crowd was a diverse mix: AI tech enthusiasts, working industry creatives, and folks who enjoy movies and who were curious about what they’d see—as well as quite a few people who fit into all three groups.

The scene at the entrance to the theater at AIFF 2025 in Santa Monica, California.

The films shown were all short, and most would be more at home at an art film fest than something more mainstream. Some shorts featured an animated aesthetic (including one inspired by anime) and some presented as live action. There was even a documentary of sorts. The films could be made entirely with Runway or other AI tools, or those tools could simply be a key part of a stack that also includes more traditional filmmaking methods.

Many of these shorts were quite weird. Most of us have seen by now that AI video-generation tools excel at producing surreal and distorted imagery—sometimes whether the person prompting the tool wants that or not. Several of these films leaned into that limitation, treating it as a strength.

Representing that camp was Vallée Duhamel’s Fragments of Nowhere, which visually explored the notion of multiple dimensions bleeding into one another. Cars morphed into the sides of houses, and humanoid figures, purported to be inter-dimensional travelers, moved in ways that defied anatomy. While I found this film visually compelling at times, I wasn’t seeing much in it that I hadn’t already seen from dreamcore or horror AI video TikTok creators like GLUMLOT or SinRostroz in recent years.

More compelling were shorts that used this propensity for oddity to generate imagery that was curated and thematically tied to some aspect of human experience or identity. For example, More Tears than Harm by Herinarivo Rakotomanana was a rotoscope animation-style “sensory collage of childhood memories” of growing up in Madagascar. Its specificity and consistent styling lent it a credibility that Fragments of Nowhere didn’t achieve. I also enjoyed Riccardo Fusetti’s Editorial on this front.

More Tears Than Harm, an unusual animated film at AIFF 2025.

Among the 10 films in the festival, two clearly stood above the others in my impressions—and they ended up being the Grand Prix and Gold prize winners. (The judging panel included filmmakers Gaspar Noé and Harmony Korine, Tribeca Enterprises CEO Jane Rosenthal, IMAX head of post and image capture Bruce Markoe, Lionsgate VFX SVP Brianna Domont, Nvidia developer relations lead Richard Kerris, and Runway CEO Cristóbal Valenzuela, among others).

Runner-up Jailbird was the aforementioned quasi-documentary. Directed by Andrew Salter, it was a brief piece that introduced viewers to a program in the UK that places chickens in human prisons as companion animals, to positive effect. Why make that film with AI, you might ask? Well, AI was used to achieve shots that wouldn’t otherwise be doable for a small-budget film to depict the experience from the chicken’s point of view. The crowd loved it.

Jailbird, the runner-up at AIFF 2025.

Then there was the Grand Prix winner, Jacob Adler’s Total Pixel Space, which was, among other things, a philosophical defense of the very idea of AI art. You can watch Total Pixel Space on YouTube right now, unlike some of the other films. I found it strangely moving, even as I saw its selection as the festival’s top winner with some cynicism. Of course they’d pick that one, I thought, although I agreed it was the most interesting of the lot.

Total Pixel Space, the Grand Prix winner at AIFF 2025.

Total Pixel Space

Even though it risked navel-gazing and self-congratulation in this venue, Total Pixel Space was filled with compelling imagery that matched the themes, and it touched on some genuinely interesting ideas—at times, it seemed almost profound, didactic as it was.

“How many images can possibly exist?” the film’s narrator asked. To answer that, it explains the concept of total pixel space, which actually reflects how image generation tools work:

Pixels are the building blocks of digital images—tiny tiles forming a mosaic. Each pixel is defined by numbers representing color and position. Therefore, any digital image can be represented as a sequence of numbers…

Just as we don’t need to write down every number between zero and one to prove they exist, we don’t need to generate every possible image to prove they exist. Their existence is guaranteed by the mathematics that defines them… Every frame of every possible film exists as coordinates… To deny this would be to deny the existence of numbers themselves.

The nine-minute film demonstrates that the number of possible images or films is greater than the number of atoms in the universe and argues that photographers and filmmakers may be seen as discovering images that already exist in the possibility space rather than creating something new.

Within that framework, it’s easy to argue that generative AI is just another way for artists to “discover” images.

The balancing act

“We are all—and I include myself in that group as well—obsessed with technology, and we keep chatting about models and data sets and training and capabilities,” Runway CEO Cristóbal Valenzuela said to me when we spoke the next morning. “But if you look back and take a minute, the festival was celebrating filmmakers and artists.”

I admitted that I found myself moved by Total Pixel Space‘s articulations. “The winner would never have thought of himself as a filmmaker, and he made a film that made you feel something,” Valenzuela responded. “I feel that’s very powerful. And the reason he could do it was because he had access to something that just wasn’t possible a couple of months ago.”

First-time and outsider filmmakers were the focus of AIFF 2025, but Runway works with established studios, too—and those relationships have an inherent tension.

The company has signed deals with companies like Lionsgate and AMC. In some cases, it trains on data provided by those companies; in others, it embeds within them to try to develop tools that fit how they already work. That’s not something competitors like OpenAI are doing yet, so that, combined with a head start in video generation, has allowed Runway to grow and stay competitive so far.

“We go directly into the companies, and we have teams of creatives that are working alongside them. We basically embed ourselves within the organizations that we’re working with very deeply,” Valenzuela explained. “We do versions of our film festival internally for teams as well so they can go through the process of making something and seeing the potential.”

Founded in 2018 at New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts by two Chileans and one Greek co-founder, Runway has a very different story than its Silicon Valley competitors. It was one of the first to bring an actually usable video-generation tool to the masses. Runway also contributed in foundational ways to the popular Stable Diffusion model.

Though it is vastly outspent by competitors like OpenAI, it has taken a hands-on approach to working with existing industries. You won’t hear Valenzuela or other Runway leaders talking about the imminence of AGI or anything so lofty; instead, it’s all about selling the product as something that can solve existing problems in creatives’ workflows.

Still, an artist’s mindset and relationships within the industry don’t negate some fundamental conflicts. There are multiple intellectual property cases involving Runway and its peers, and though the company hasn’t admitted it, there is evidence that it trained its models on copyrighted YouTube videos, among other things.

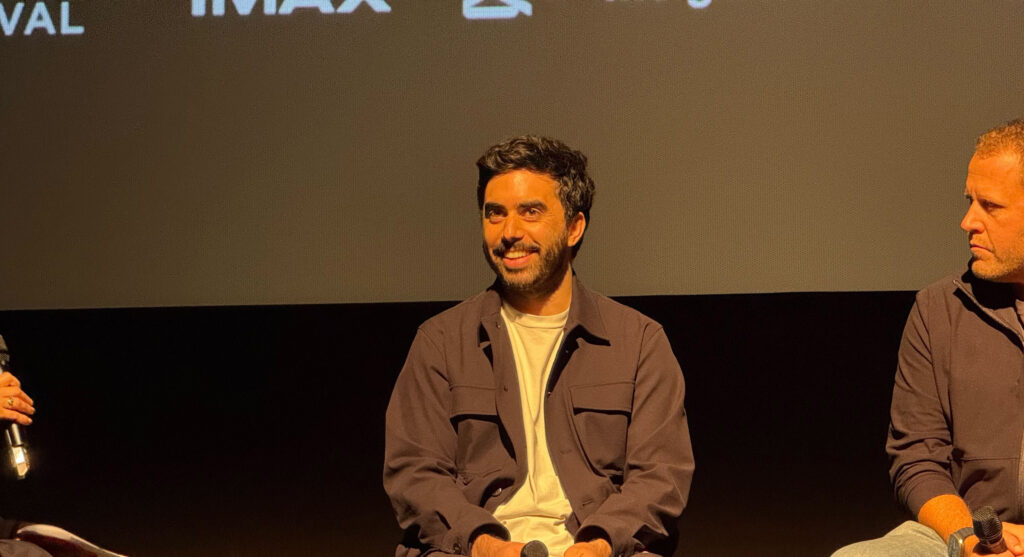

Cristóbal Valenzuela speaking on the AIFF 2025 stage. Credit: Samuel Axon

Valenzuela suggested that studios are worried about liability, not underlying principles, though, saying:

Most of the concerns on copyright are on the output side, which is like, how do you make sure that the model doesn’t create something that already exists or infringes on something. And I think for that, we’ve made sure our models don’t and are supportive of the creative direction you want to take without being too limiting. We work with every major studio, and we offer them indemnification.

In the past, he has also defended Runway by saying that what it’s producing is not a re-creation of what has come before. He sees the tool’s generative process as distinct—legally, creatively, and ethically—from simply pulling up assets or references from a database.

“People believe AI is sort of like a system that creates and conjures things magically with no input from users,” he said. “And it’s not. You have to do that work. You still are involved, and you’re still responsible as a user in terms of how you use it.”

He seemed to share this defense of AI as a legitimate tool for artists with conviction, but given that he’s been pitching these products directly to working filmmakers, he was also clearly aware that not everyone agrees with him. There is not even a consensus among those in the industry.

An industry divided

While in LA for the event, I visited separately with two of my oldest friends. Both of them work in the film and television industry in similar disciplines. They each asked what I was in town for, and I told them I was there to cover an AI film festival.

One immediately responded with a grimace of disgust, “Oh, yikes, I’m sorry.” The other responded with bright eyes and intense interest and began telling me how he already uses AI in his day-to-day to do things like extend shots by a second or two for a better edit, and expressed frustration at his company for not adopting the tools faster.

Neither is alone in their attitudes. Hollywood is divided—and not for the first time.

There have been seismic technological changes in the film industry before. There was the transition from silent films to talkies, obviously; moviemaking transformed into an entirely different art. Numerous old jobs were lost, and numerous new jobs were created.

Later, there was the transition from film to digital projection, which may be an even tighter parallel. It was a major disruption, with some companies and careers collapsing while others rose. There were people saying, “Why do we even need this?” while others believed it was the only sane way forward. Some audiences declared the quality worse, and others said it was better. There were analysts arguing it could be stopped, while others insisted it was inevitable.

IMAX’s head of post production, Bruce Markoe, spoke briefly about that history at a press mixer before the festival. “It was a little scary,” he recalled. “It was a big, fundamental change that we were going through.”

People ultimately embraced it, though. “The motion picture and television industry has always been very technology-forward, and they’ve always used new technologies to advance the state of the art and improve the efficiencies,” Markoe said.

When asked whether he thinks the same thing will happen with generative AI tools, he said, “I think some filmmakers are going to embrace it faster than others.” He pointed to AI tools’ usefulness for pre-visualization as particularly valuable and noted some people are already using it that way, but it will take time for people to get comfortable with.

And indeed, many, many filmmakers are still loudly skeptical. “The concept of AI is great,” The Mitchells vs. the Machines director Mike Rianda said in a Wired interview. “But in the hands of a corporation, it is like a buzzsaw that will destroy us all.”

Others are interested in the technology but are concerned that it’s being brought into the industry too quickly, with insufficient planning and protections. That includes Crafty Apes Senior VFX Supervisor Luke DiTomasso. “How fast do we roll out AI technologies without really having an understanding of them?” he asked in an interview with Production Designers Collective. “There’s a potential for AI to accelerate beyond what we might be comfortable with, so I do have some trepidation and am maybe not gung-ho about all aspects of it.“

Others remain skeptical that the tools will be as useful as some optimists believe. “AI never passed on anything. It loved everything it read. It wants you to win. But storytelling requires nuance—subtext, emotion, what’s left unsaid. That’s something AI simply can’t replicate,” said Alegre Rodriquez, a member of the Emerging Technology committee at the Motion Picture Editors Guild.

The mirror

Flying back from Los Angeles, I considered two key differences between this generative AI inflection point for Hollywood and the silent/talkie or film/digital transitions.

First, neither of those transitions involved an existential threat to the technology on the basis of intellectual property and copyright. Valenzuela talked about what matters to studio heads—protection from liability over the outputs. But the countless creatives who are critical of these tools also believe they should be consulted and even compensated for their work’s use in the training data for Runway’s models. In other words, it’s not just about the outputs, it’s also about the sourcing. As noted before, there are several cases underway. We don’t know where they’ll land yet.

Second, there’s a more cultural and philosophical issue at play, which Valenzuela himself touched on in our conversation.

“I think AI has become this sort of mirror where anyone can project all their fears and anxieties, but also their optimism and ideas of the future,” he told me.

You don’t have to scroll for long to come across techno-utopians declaring with no evidence that AGI is right around the corner and that it will cure cancer and save our society. You also don’t have to scroll long to encounter visceral anger at every generative AI company from people declaring the technology—which is essentially just a new methodology for programming a computer—fundamentally unethical and harmful, with apocalyptic societal and economic ramifications.

Amid all those bold declarations, this film festival put the focus on the on-the-ground reality. First-time filmmakers who might never have previously cleared Hollywood’s gatekeepers are getting screened at festivals because they can create competitive-looking work with a fraction of the crew and hours. Studios and the people who work there are saying they’re saving time, resources, and headaches in pre-viz, editing, visual effects, and other work that’s usually done under immense time and resource pressure.

“People are not paying attention to the very huge amount of positive outcomes of this technology,” Valenzuela told me, pointing to those examples.

In this online discussion ecosystem that elevates outrage above everything else, that’s likely true. Still, there is a sincere and rigorous conviction among many creatives that their work is contributing to this technology’s capabilities without credit or compensation and that the structural and legal frameworks to ensure minimal human harm in this evolving period of disruption are still inadequate. That’s why we’ve seen groups like the Writers Guild of America West support the Generative AI Copyright Disclosure Act and other similar legislation meant to increase transparency about how these models are trained.

The philosophical question with a legal answer

The winning film argued that “total pixel space represents both the ultimate determinism and the ultimate freedom—every possibility existing simultaneously, waiting for consciousness to give it meaning through the act of choice.”

In making this statement, the film suggested that creativity, above all else, is an act of curation. It’s a claim that nothing, truly, is original. It’s a distillation of human expression into the language of mathematics.

To many, that philosophy rings undeniably true: Every possibility already exists, and artists are just collapsing the waveform to the frame they want to reveal. To others, there is more personal truth to the romantic ideal that artwork is valued precisely because it did not exist until the artist produced it.

All this is to say that the debate about creativity and AI in Hollywood is ultimately a philosophical one. But it won’t be resolved that way.

The industry may succumb to litigation fatigue and a hollowed-out workforce—or it may instead find its way to fair deals, new opportunities for fresh voices, and transparent training sets.

For all this lofty talk about creativity and ideas, the outcome will come down to the contracts, court decisions, and compensation structures—all things that have always been at least as big a part of Hollywood as the creative work itself.

Samuel Axon is the editorial lead for tech and gaming coverage at Ars Technica. He covers AI, software development, gaming, entertainment, and mixed reality. He has been writing about gaming and technology for nearly two decades at Engadget, PC World, Mashable, Vice, Polygon, Wired, and others. He previously ran a marketing and PR agency in the gaming industry, led editorial for the TV network CBS, and worked on social media marketing strategy for Samsung Mobile at the creative agency SPCSHP. He also is an independent software and game developer for iOS, Windows, and other platforms, and he is a graduate of DePaul University, where he studied interactive media and software development.