There’s no big rush to bring SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy to Vandenberg Space Force Base.

A SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket soars into orbit from Vandenberg Space Force Base, California, with multiple satellites for the National Reconnaissance Office on April 20, 2025. The rocket lifted off just before sunrise, and its exhaust plume was illuminated by the Sun as it climbed to higher altitudes. Credit: George Rose/Getty Images

The Department of the Air Force has approved SpaceX’s plans to launch up to 100 missions per year from Vandenberg Space Force Base in California.

This would continue the tectonic turnaround at the spaceport on California’s Central Coast. Five years ago, Vandenberg hosted just a single orbital launch. This year’s number stands at 51 orbital flights, or 53 launches if you count a pair of Minuteman missile tests, the most in a single calendar year at Vandenberg since the early 1970s.

Vandenberg is used for missions launching into polar orbits, paths oriented north-south that, over time, cover most of the Earth’s surface area. These orbits are popular for Earth observation satellites.

The surge in rocket launches on the West Coast has been driven by SpaceX, primarily missions deploying satellites for the commercial Starlink broadband network and secret spy platforms for the US government. There’s more of that to come. Military officials have now authorized SpaceX to double its annual launch rate at Vandenberg from 50 to 100, with up to 95 missions using the Falcon 9 rocket and up to five launches of the larger Falcon Heavy.

A Falcon 9 rocket lifts off from Space Launch Complex 4-East with 24 Starlink broadband satellites on September 19, 2025. Credit: SpaceX

Go for 100

The Department of the Air Force released a final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) on SpaceX’s plans, then signed a “Record of Decision” on October 10 to approve changes to the Falcon launch program at Vandenberg, a base next to the Pacific Ocean about 140 miles (225 kilometers) northwest of Los Angeles. The Federal Aviation Administration will make a separate determination on increasing the number of commercial SpaceX launches from California.

The California Coastal Commission, a state environmental protection agency, has already rejected SpaceX’s proposal to double the number of launches at Vandenberg, citing concerns about noise disruptions to people, wildlife, and property. The commission has a long-running feud with SpaceX and its founder Elon Musk, but it’s unclear what mechanism the agency has to enforce its restriction. The Department of the Air Force, which oversees the Space Force, has stated that the higher launch cadence will benefit US national security interests, and the launch pads are on federal property.

There’s more to the changes at Vandenberg than launching additional rockets. The authorization gives SpaceX the green light to redevelop Space Launch Complex 6 (SLC-6) to support Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy missions. SpaceX plans to demolish unneeded structures at SLC-6 (pronounced “Slick 6”) and construct two new landing pads for Falcon boosters on a bluff overlooking the Pacific just south of the pad.

SpaceX currently operates from a single pad at Vandenberg—Space Launch Complex 4-East (SLC-4E)—a few miles north of the SLC-6 location. The SLC-4E location is not configured to launch the Falcon Heavy, an uprated rocket with three Falcon 9 boosters bolted together.

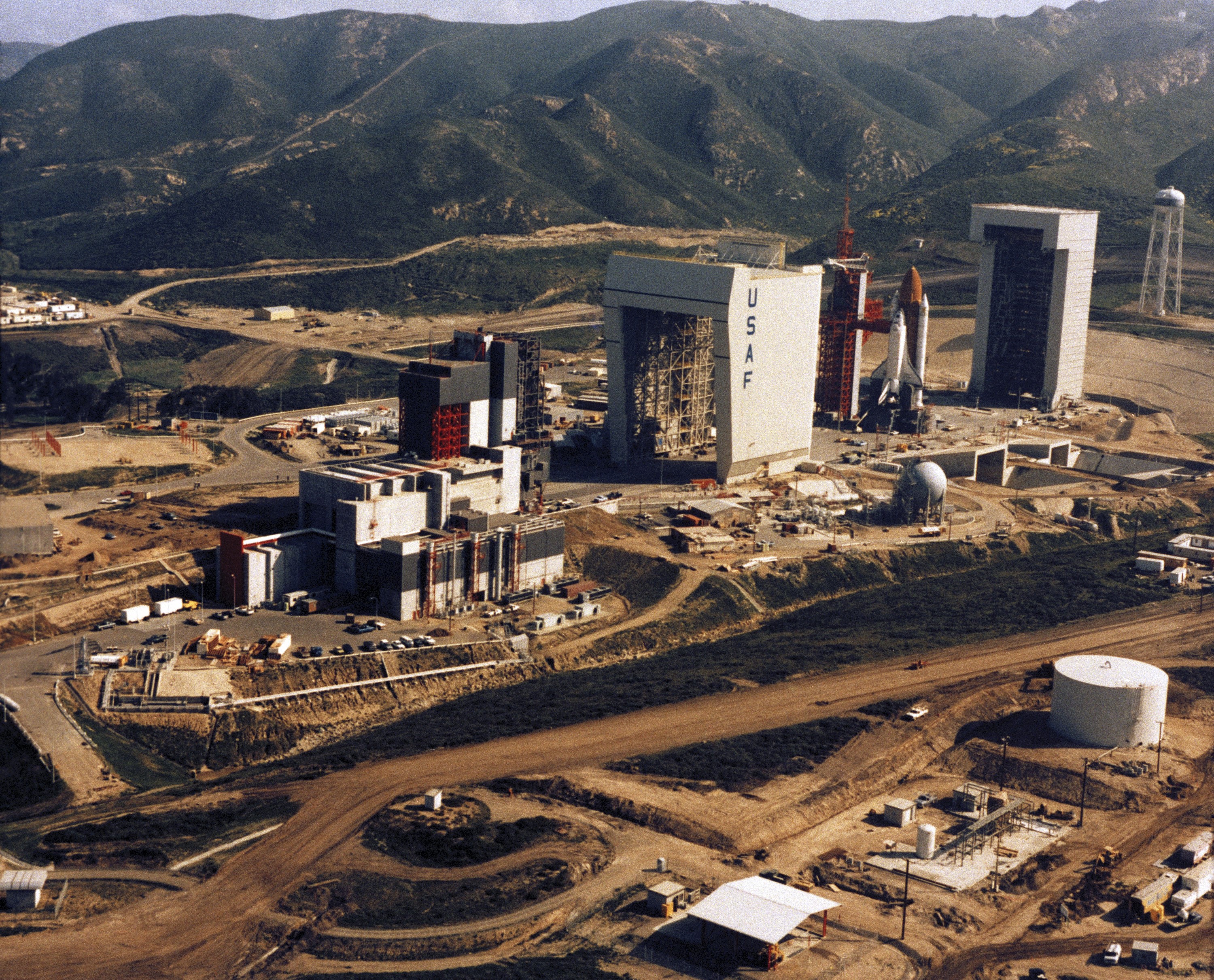

SLC-6, cocooned by hills on three sides and flanked by the ocean to the west, is no stranger to big rockets. It was first developed for the Air Force’s Manned Orbiting Laboratory program in the 1960s, when the military wanted to put a mini-space station into orbit for astronauts to spy on the Soviet Union. Crews readied the complex to launch military astronauts on top of Titan rockets, but the Pentagon canceled the program in 1969 before anything actually launched from SLC-6.

NASA and the Air Force then modified SLC-6 to launch space shuttles. The space shuttle Enterprise was stacked vertically at SLC-6 for fit checks in 1985, but the Air Force abandoned the Vandenberg-based shuttle program after the Challenger accident in 1986. The launch facility sat mostly dormant for nearly two decades until Boeing, and then United Launch Alliance, took over SLC-6 and began launching Delta IV rockets there in 2006.

The space shuttle Enterprise stands vertically at Space Launch Complex-6 at Vandenberg. NASA used the shuttle for fit checks at the pad, but it never launched from California. Credit: NASA

ULA launched its last Delta IV Heavy rocket from California in 2022, leaving the future of SLC-6 in question. ULA’s new rocket, the Vulcan, will launch from a different pad at Vandenberg. Space Force officials selected SpaceX in 2023 to take over the pad and prepare it to launch the Falcon Heavy, which has the lift capacity to carry the military’s most massive satellites into orbit.

No big rush

Progress at SLC-6 has been slow. It took nearly a year to prepare the Environmental Impact Statement. In reality, there’s no big rush to bring SLC-6 online. SpaceX has no Falcon Heavy missions from Vandenberg in its contract backlog, but the company is part of the Pentagon’s stable of launch providers. To qualify as a member of the club, SpaceX must have the capability to launch the Space Force’s heaviest missions from the military’s spaceports at Vandenberg and Cape Canaveral, Florida.

United Launch Alliance, the Space Force’s other major launch provider, is preparing to activate a launch pad at Vandenberg for its Vulcan rocket. Blue Origin has plans to build a launch site at Vandenberg but hasn’t started construction.

SpaceX expects to begin work at SLC-6 late this year or early next year and will take approximately 18 months to complete the construction, according to the EIS. The most prominent structures at the launch pad, originally built for the Manned Orbiting Laboratory and the space shuttle, will be demolished using explosives. SpaceX will add new propellant storage tanks, a rocket integration hangar, vehicle erector, water tower, ground support equipment, and a transport road with rail systems.

This construction timeline suggests SLC-6 will become operational sometime in 2027. SpaceX has plenty of time to get the launch pad ready. The Space Force won’t have a mission from Vandenberg that needs a heavy-lift rocket until 2030, and even then, SpaceX’s Falcon Heavy must compete with ULA’s Vulcan rocket for the right to launch it.

The payloads most likely suited for the Falcon Heavy are the National Reconnaissance Office’s largest spy satellites, massive platforms the size of a bus that collect super-high-resolution ground imagery for the government’s intelligence agencies. There are few, if any, commercial satellites in the current market that would require a Falcon Heavy launch.

Stephen Clark is a space reporter at Ars Technica, covering private space companies and the world’s space agencies. Stephen writes about the nexus of technology, science, policy, and business on and off the planet.