These chemical oddities may explain why Earth seems to be deficient in certain elements.

For close to a century, geoscientists have pondered a mystery: Where did Earth’s lighter elements go? Compared to amounts in the Sun and in some meteorites, Earth has less hydrogen, carbon, nitrogen, and sulfur, as well as noble gases like helium—in some cases, more than 99 percent less.

Some of the disparity is explained by losses to the solar system as our planet formed. But researchers have long suspected that something else was going on too.

Recently, a team of scientists reported a possible explanation—that the elements are hiding deep in the solid inner core of Earth. At its super-high pressure—360 gigapascals, 3.6 million times atmospheric pressure—the iron there behaves strangely, becoming an electride: a little-known form of the metal that can suck up lighter elements.

Study coauthor Duck Young Kim, a solid-state physicist at the Center for High Pressure Science & Technology Advanced Research in Shanghai, says the absorption of these light elements may have happened gradually over a couple of billion years—and may still be going on today. It would explain why the movement of seismic waves traveling through Earth suggests an inner core density that is 5 percent to 8 percent lower than expected were it metal alone.

Electrides, in more ways than one, are having their moment. Not only might they help solve a planetary mystery, they can now be made at room temperature and pressure from an array of elements. And since all electrides contain a source of reactive electrons that are easily donated to other molecules, they make ideal catalysts and other sorts of agents that help to propel challenging reactions.

One electride is already in use to catalyze the production of ammonia, a key component of fertilizer; its Japanese developers claim the process uses 20 percent less energy than traditional ammonia manufacture. Chemists, meanwhile, are discovering new electrides that could lead to cheaper and greener methods of producing pharmaceuticals.

Today’s challenge is to find more of these intriguing materials and to understand the chemical rules that govern when they form.

The ammonia production plant at Ludwigshafen, Germany, has operated for more than a century. It was the first to use the Haber-Bosch process, which garnered Nobel Prizes for its inventor and developer, Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch. Today, plants including this one run by the chemical company BASF are seeking more renewable ways to produce ammonia.

Credit: BASF SE

The ammonia production plant at Ludwigshafen, Germany, has operated for more than a century. It was the first to use the Haber-Bosch process, which garnered Nobel Prizes for its inventor and developer, Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch. Today, plants including this one run by the chemical company BASF are seeking more renewable ways to produce ammonia. Credit: BASF SE

Electrides at high pressure

Most solids are made from ordered lattices of atoms, but electrides are different. Their lattices have little pockets where electrons sit on their own.

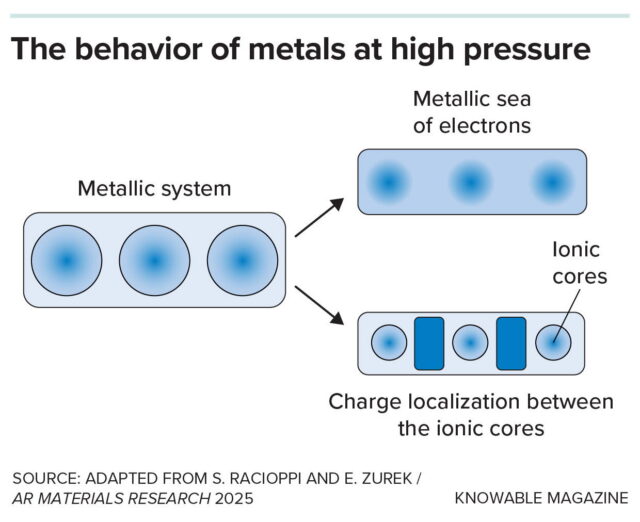

Normal metals have electrons that are not stuck to one atom. These are the outer, or valence, electrons that are free to move between atoms, forming what is often referred to as a delocalized “sea of electrons.” It explains why metals conduct electricity.

The outer electrons of electrides no longer orbit a particular atom either, but they can’t freely move. Instead, they become trapped at sites between atoms that are called non-nuclear attractors. This gives the materials unique properties. In the case of the iron in Earth’s core, the negative electron charges stabilize lighter elements at non-nuclear attractors that were formed at those super-high pressures, 3,000 times than at the bottom of the deepest ocean. The elements would diffuse into the metal, explaining where they disappeared to.

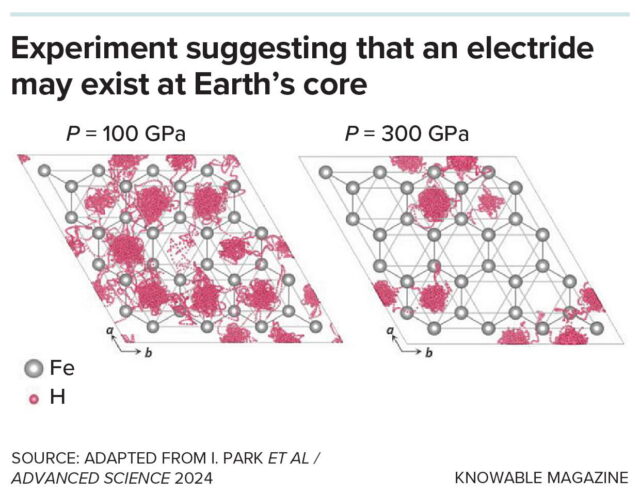

In an experiment, scientists simulated the movement of hydrogen atoms (pink) into the lattice structure of iron at a temperature of 3,000 degrees Kelvin (2,727 Celsius), at pressures of 100 gigapascals (GPa) and 300 GPa. At the higher pressure (right) an electride forms, as indicated by the altered distribution of the hydrogen observed within the iron lattice—these would represent the negatively charged non-nuclear attractor sites to which hydrogen atoms bond, forming hydride ions. Duck Young Kim and his coauthors think that the altered hydrogen distribution at higher pressure in these simulations is good evidence that an electride with non-nuclear reactor sites forms within the iron of Earth’s core.

In an experiment, scientists simulated the movement of hydrogen atoms (pink) into the lattice structure of iron at a temperature of 3,000 degrees Kelvin (2,727 Celsius), at pressures of 100 gigapascals (GPa) and 300 GPa. At the higher pressure (right) an electride forms, as indicated by the altered distribution of the hydrogen observed within the iron lattice—these would represent the negatively charged non-nuclear attractor sites to which hydrogen atoms bond, forming hydride ions. Duck Young Kim and his coauthors think that the altered hydrogen distribution at higher pressure in these simulations is good evidence that an electride with non-nuclear reactor sites forms within the iron of Earth’s core. Credit: Knowable Magazine (CC BY-ND)

The first metal found to form an electride at high pressure was sodium, reported in 2009. At a pressure of 200 gigapascals (2 million times greater than atmospheric pressure) it transforms from a shiny, reflective, conducting metal into a transparent glassy, insulating material. This finding was “very weird,” says Stefano Racioppi, a computational and theoretical chemist at the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, who worked on sodium electrides while in the lab of Eva Zurek at the University at Buffalo in New York state. Early theories, he says, had predicted that at high pressure, sodium’s outer electrons would move even more freely between atoms.

The first sign that things were different came from predictions in the late 1990s, when scientists were using computational simulations to model solids, based on the rules of quantum theory. These rules define the energy levels that electrons can have, and hence the probable range of positions in which they are found in atoms (their atomic orbitals).

Simulating solid sodium showed that at high pressures, as the sodium atoms get squeezed closer together, so do the electrons orbiting each atom. That causes them to experience increasing repulsive forces with one another. This changes the relative energies of every electron orbiting the nucleus of each atom, Racioppi explains—leading to a reorganization of electron positions.

The result? Rather than occupying orbitals that allow them to be delocalized and move between atoms, the orbitals take on a new shape that forces electrons into the non-nuclear attractor sites. Since the electrons are stuck at these sites, the solid loses its metallic properties.

Adding to this theoretical work, Racioppi and Zurek collaborated with researchers at the University of Edinburgh to find experimental evidence for a sodium electride at extreme pressures. Squeezing crystals of sodium between two diamonds, they used X-ray diffraction to map electron density in the metal structure. This, they reported in September 2025, confirmed that electrons really were located in the predicted non-nuclear attractor sites between sodium atoms.

This graphic shows alternative models for metal structures. At left is the structure at ambient conditions, with each blue circle representing a single atom in the metallic lattice consisting of a positively charged nucleus surrounded by its electrons. The electrons can move freely throughout the lattice in what is known as a “sea of electrons.” Earlier theories of metals at high pressures assumed a similar structure, with even greater metallic characteristics (top, right), but more recent modeling shows that in some metals like sodium, at high pressure the structure changes (bottom, right) to a system in which the electrons are localized (dark blue boxes) between the ionic cores (small light blue circles)—an electride. This gives the structure very different properties.

This graphic shows alternative models for metal structures. At left is the structure at ambient conditions, with each blue circle representing a single atom in the metallic lattice consisting of a positively charged nucleus surrounded by its electrons. The electrons can move freely throughout the lattice in what is known as a “sea of electrons.” Earlier theories of metals at high pressures assumed a similar structure, with even greater metallic characteristics (top, right), but more recent modeling shows that in some metals like sodium, at high pressure the structure changes (bottom, right) to a system in which the electrons are localized (dark blue boxes) between the ionic cores (small light blue circles)—an electride. This gives the structure very different properties. Credit: Knowable Magazine (CC BY-ND)

Just the thing for catalysts

Electrides are ideal candidates for catalysts—substances that can speed up and lower the energy needed for chemical reactions. That’s because the isolated electrons at the non-nuclear attractor sites can be donated to make and break bonds. But to be useful, they would need to function at ambient conditions.

Several such stable electrides have been discovered over the last 10 years, made from inorganic compounds or organic molecules containing metal atoms. One of the most significant, mayenite, was found by surprise in 2003 when material scientist Hideo Hosono at the Institute of Science Tokyo was investigating a type of cement.

Mayenite is a calcium aluminate oxide that forms crystals with very small pores—a few nanometers across—called cages, that contain oxygen ions. If a metal vapor of calcium or titanium is passed over it at high temperature, it removes the oxygen, leaving behind just electrons trapped at these sites—an electride.

Unlike the high-pressure metal electrides that switch from conductors to insulators, mayenite starts as an insulator. But now its trapped electrons can jump between cage sites (via a process called quantum tunnelling)—making it a conductor, albeit 100 to 1,000 times less conductive than a metal like aluminum or silver. It also becomes an excellent catalyst, able to surrender electrons to help make and break bonds in reactions.

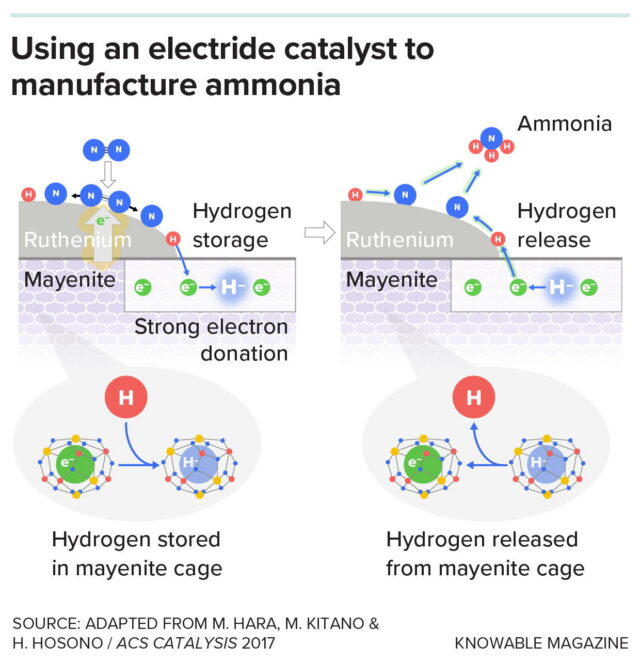

By 2011, Hosono had begun to develop mayenite as a greener and more efficient catalyst for synthesizing ammonia. Over 170 million metric tons of ammonia, mostly for fertilizers, is produced annually via the Haber-Bosch process, in which metal oxides facilitate hydrogen and nitrogen gases reacting together at high pressure and temperature. It is an energy-intensive, expensive process—Haber-Bosch plants account for some 2 percent of the world’s energy use.

In Haber-Bosch, the catalysts bind the two gases to their surfaces and donate electrons to help break the strong triple bond that holds the two nitrogen atoms together in nitrogen gas, as well as the bonds in hydrogen gas. Because mayenite has a strong electron-donating nature, Hosono thought mayenite would be able to do it better.

In Hosono’s reaction, mayenite itself does not bind the gases but acts as a support bed for nanoparticles of a metal called ruthenium. First, the nanoparticles absorb the nitrogen and hydrogen gases. Then the mayenite donates electrons to the ruthenium. These electrons flow into the nitrogen and hydrogen molecules, making it easier to break their bonds. Ammonia thus forms at a lower temperature—300 to 400° C—and lower pressure—50 to 80 atmospheres— than with Haber-Bosch, which takes place at 400 to 500° C and 100 to 400 atmospheres.

This graphic shows the proposed reaction mechanism when ammonia (NH₃) is synthesized using a catalyst consisting of the metal ruthenium along with mayenite, a stable electride. The strong electron-donating properties of mayenite (left) make it easier for nitrogen molecules to break apart and the atoms to be absorbed onto the ruthenium surface. Hydrogen, meanwhile, can be stored in the cages in the mayenite (bottom left) where negatively charged electrons are located. The hydrogen can move from cage to cage and be released onto the ruthenium surface to react with the nitrogen. These processes make ammonia formation more efficient.

This graphic shows the proposed reaction mechanism when ammonia (NH₃) is synthesized using a catalyst consisting of the metal ruthenium along with mayenite, a stable electride. The strong electron-donating properties of mayenite (left) make it easier for nitrogen molecules to break apart and the atoms to be absorbed onto the ruthenium surface. Hydrogen, meanwhile, can be stored in the cages in the mayenite (bottom left) where negatively charged electrons are located. The hydrogen can move from cage to cage and be released onto the ruthenium surface to react with the nitrogen. These processes make ammonia formation more efficient. Credit: Knowable Magazine (CC BY-ND)

In 2017, the company Tsubame BHB was formed to commercialize Hosono’s catalyst, with the first pilot plant opening in 2019, producing 20 metric tons of ammonia per year. The company has since opened a larger facility in Japan and is setting up a 20,000-ton-per year green ammonia plant in Brazil to replace some of the nation’s fossil-fuel-based fertilizer production. The company estimates that this will avoid 11,000 tons of CO2 emissions annually—about equal to the annual emissions of 2,400 cars.

There are other applications for a mayenite catalyst, says Hosono, including a lower-energy conversion of CO2 into useful chemicals like methane, methanol, or longer-chain hydrocarbons. Other scientists have suggested that mayenite’s cage structure also makes it suitable for immobilizing radioactive isotope waste in nuclear power stations: The electrons could capture negative ions like iodine and bromide and trap them in the cages.

Mayenite has even been studied as a low-temperature propulsion system for satellites in space. When it is heated to 600° C in a vacuum, its trapped electrons blast from the cages, causing propulsion.

Organic electrides

The list of materials known to form electrides keeps growing. In 2024, a team led by chemist Fabrizio Ortu at the University of Leicester in the UK accidentally discovered another room-temperature-stable electride made from calcium ions surrounded by large organic molecules, together known as a coordination complex.

He was using a method known as mechanical chemistry—“You put something in a milling jar, you shake it really hard, and that provides the energy for the reaction,” he says. But to his surprise, electrons from the potassium he had added to his calcium complex were not donated to the calcium ion. Instead, what formed “had these electrons that were floating in the system,” he says, trapped in sites between the two metals.

Unlike mayenite, this electride is not a conductor—its trapped electrons do not jump. But they allow it to facilitate reactions that are otherwise hard to get started, by activating unreactive bonds, doing a job much like a catalyst. These are reactions that currently rely on expensive palladium catalysts.

The scientists successfully used the electride on a reaction that joins two pyridine rings—carbon rings containing a nitrogen atom. They are now examining whether the electride could assist in other common organic reactions, such as substituting a hydrogen atom on a benzene ring. These substitutions are difficult because the bond between the benzene ring carbon and its attached hydrogen is very stable.

There are still problems to sort out: Ortu’s calcium electride is too air- and water-sensitive for use in industry. He is now looking for a more stable alternative, which could prove particularly useful in the pharmaceutical industry to synthesize drug molecules, where the sorts of reactions Ortu has demonstrated are common.

Still questions at the core

There remain many unresolved mysteries about electrides, including whether Earth’s inner core definitely contains one. Kim and his collaborators used simulations of the iron lattice to find evidence for non-nuclear attractor sites, but their interpretation of the results remains “a little bit controversial,” Racioppi says.

Sodium and other metals in Group 1 and Group 2 of the periodic table of elements—such as lithium, calcium, and magnesium—have loosely bound outer electrons. This helps make it easy for electrons to shift to non-nuclear attractor sites, forming electrides. But iron exerts more pulling power on its outer electrons, which sit in differently shaped orbitals. This makes the increase in electron repulsion under pressure less significant and thus the shift to electride formation difficult, Racioppi says.

Electrides are still little known and little studied, says computational materials scientist Lee Burton of Tel Aviv University. There is still no theory or model to predict when a material will become one. “Because electrides are not typical chemically, you can’t bring your chemical intuition to it,” he says.

Burton has been searching for rules that might help with predictions and has had some success finding electrides from a screen of 40,000 known materials. He is now using artificial intelligence to find more. “It’s a complex interplay between different properties that sometimes can all depend on each other,” he says. “This is where machine learning can really help.”

The key is having reliable data to train any model. Burton’s team only has actual data from the handful of electride structures experimentally confirmed so far, but they also are using the kind of modeling based on quantum theory that was carried out by Racioppi to create high-resolution simulations of electron density within materials. They are doing this for as many materials as they can; those that are confirmed by real-world experiments will be used to train an AI model to identify more materials that are likely to be electrides—ones with the discrete pockets of high electron density characteristic of trapped electron sites. “The potential,” says Burton, “is enormous.”

Knowable Magazine, 2026. DOI: 10.1146/knowable-012626-2 (About DOIs)

“This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, a nonprofit publication dedicated to making scientific knowledge accessible to all. Sign up for Knowable Magazine’s newsletter.”

Knowable Magazine explores the real-world significance of scholarly work through a journalistic lens.