SpaceX may soon have up to nine active launch pads. Most competitors have one or two.

A Delta IV Heavy rocket stands inside the mobile service tower at Space Launch Complex-37 in this photo from 2014. SpaceX is set to demolish all of the structures seen here. Credit: United Launch Alliance

The US Air Force is moving closer to authorizing SpaceX to move into one of the largest launch pads at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station in Florida, with plans to use the facility for up to 76 launches of the company’s Starship rocket each year.

A draft Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) released this week by the Department of the Air Force, which includes the Space Force, found SpaceX’s planned use of Space Launch Complex 37 (SLC-37) at Cape Canaveral would have no significant negative impacts on local environmental, historical, social, and cultural interests. The Air Force also found SpaceX’s plans at SLC-37 will have no significant impact on the company’s competitors in the launch industry.

The Defense Department is leading the environmental review and approval process for SpaceX to take over the launch site, which the Space Force previously leased to United Launch Alliance, one of SpaceX’s chief rivals in the US launch industry. ULA launched its final Delta IV Heavy rocket from SLC-37 in April 2024, a couple of months after the military announced SpaceX was interested in using the launch pad.

Ground crews are expected to begin removing Delta IV-era structures at the launch pad this week. Multiple sources told Ars demolition could begin as soon as Thursday.

Emre Kelly, a Space Force spokesperson, deferred questions on the schedule for the demolition to SpaceX, which is overseeing the work. But he said the Delta IV’s mobile gantry, fixed umbilical tower, and both lightning towers will come down. Unlike other large-scale demolitions at Cape Canaveral, SpaceX and the Space Force don’t plan to publicize the event ahead of time.

“Demolition of these items will be conducted in accordance with federal and state laws that govern explosive demolition operations,” Kelly said.

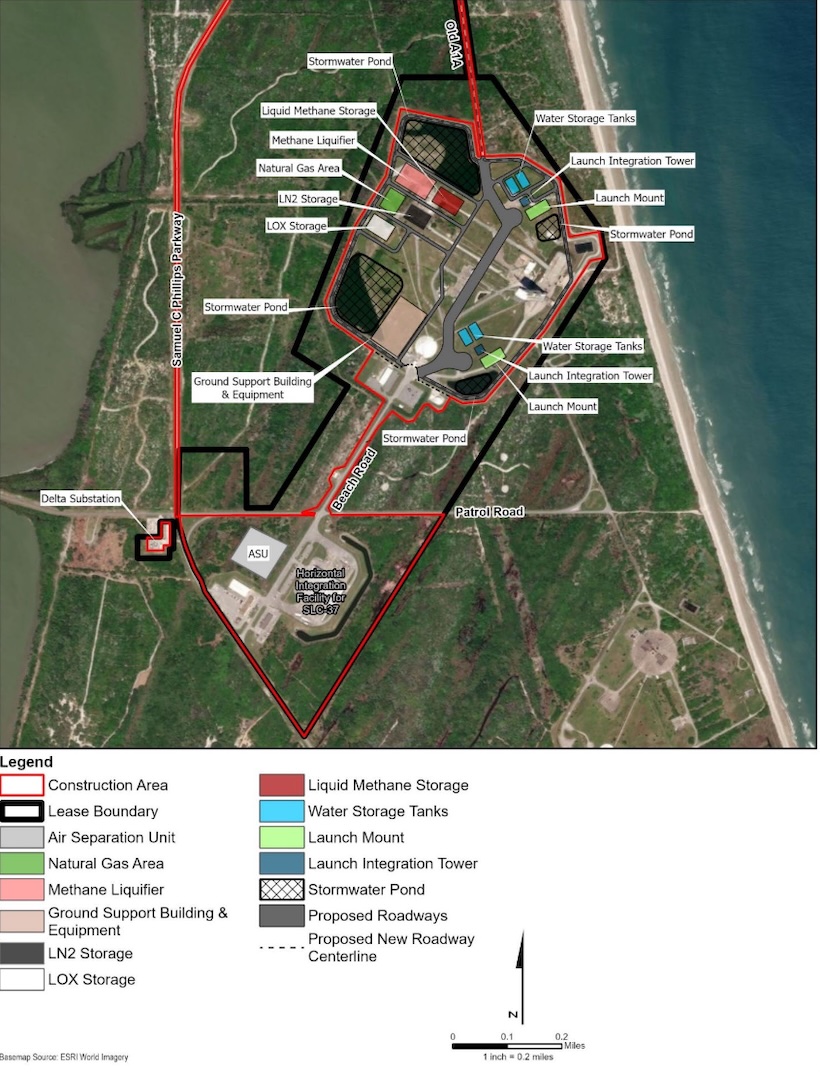

In their place, SpaceX plans to build two 600-foot-tall (180-meter) Starship launch integration towers within the 230-acre confines of SLC-37.

Tied at the hip

The Space Force’s willingness to turn over a piece of prime real estate at Cape Canaveral to SpaceX helps illustrate the government’s close relationship with—indeed, reliance on—Elon Musk’s space company. The breakdown of Musk’s relationship with President Donald Trump has, so far, only spawned a war of words between the two billionaires.

But Trump has threatened to terminate Musk’s contracts with the federal government and warned of “serious consequences” for Musk if he donates money to Democratic political candidates. Musk said he would begin decommissioning SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft, the sole US vehicle ferrying astronauts to and from orbit, before backing off the threat last week.

NASA and the Space Force need SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft and its Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets to maintain the International Space Station and launch the nation’s most critical military satellites. The super heavy-lift capabilities Starship will bring to the government could enable a range of new missions, such as global cargo delivery for the military and missions to the Moon and Mars in partnership with NASA.

Fully stacked, the Starship rocket stands more than 400 feet tall. Credit: SpaceX

SpaceX already has a “right of limited entry” to begin preparations to convert SLC-37 into a Starship launch pad. A full lease agreement between the Space Force and SpaceX is expected after the release of the final Environmental Impact Statement.

The environmental approval process began more than a year ago with a notice of intent, followed by studies, evaluations, and scope meetings that fed into the creation of the draft EIS. Now, government officials will host more public meetings and solicit public comments on SpaceX’s plans through late July. Then, sometime this fall, the Department of the Air Force will issue a final EIS and a “record of decision,” according to the project’s official timeline.

A growing footprint

This timeline could allow SpaceX to begin launching Starships from SLC-37 as soon as next year, although the site still requires the demolition of existing structures and construction of new towers, propellant farms, a methane liquefaction plant, water tanks, deluge systems, and other ground support equipment. The construction will likely take more than a year, so perhaps 2027 is a more realistic target.

The company is also studying an option to construct two separate towers for use exclusively as “catch towers” for recovery of Super Heavy boosters and Starship upper stages “if space allows” at SLC-37, according to the draft EIS. According to the Air Force, the initial review process eliminated an option for SpaceX to construct a standalone Starship launch pad on undeveloped property at Cape Canaveral because the site would have a “high potential” for impacting endangered species and is “less ideal” than developing an existing launch pad.

SpaceX’s plan for recovering its reusable Super Heavy and Starship vehicles involves catching them with articulating arms on a tower—either a launch integration structure or a catch-only tower. SpaceX has already demonstrated catching the Super Heavy booster on three test flights at the company’s Starbase launch site in South Texas. An attempt to catch a Starship vehicle returning from low-Earth orbit might happen later this year, assuming SpaceX can correct the technical problems that have stalled the rocket’s advancement in recent months.

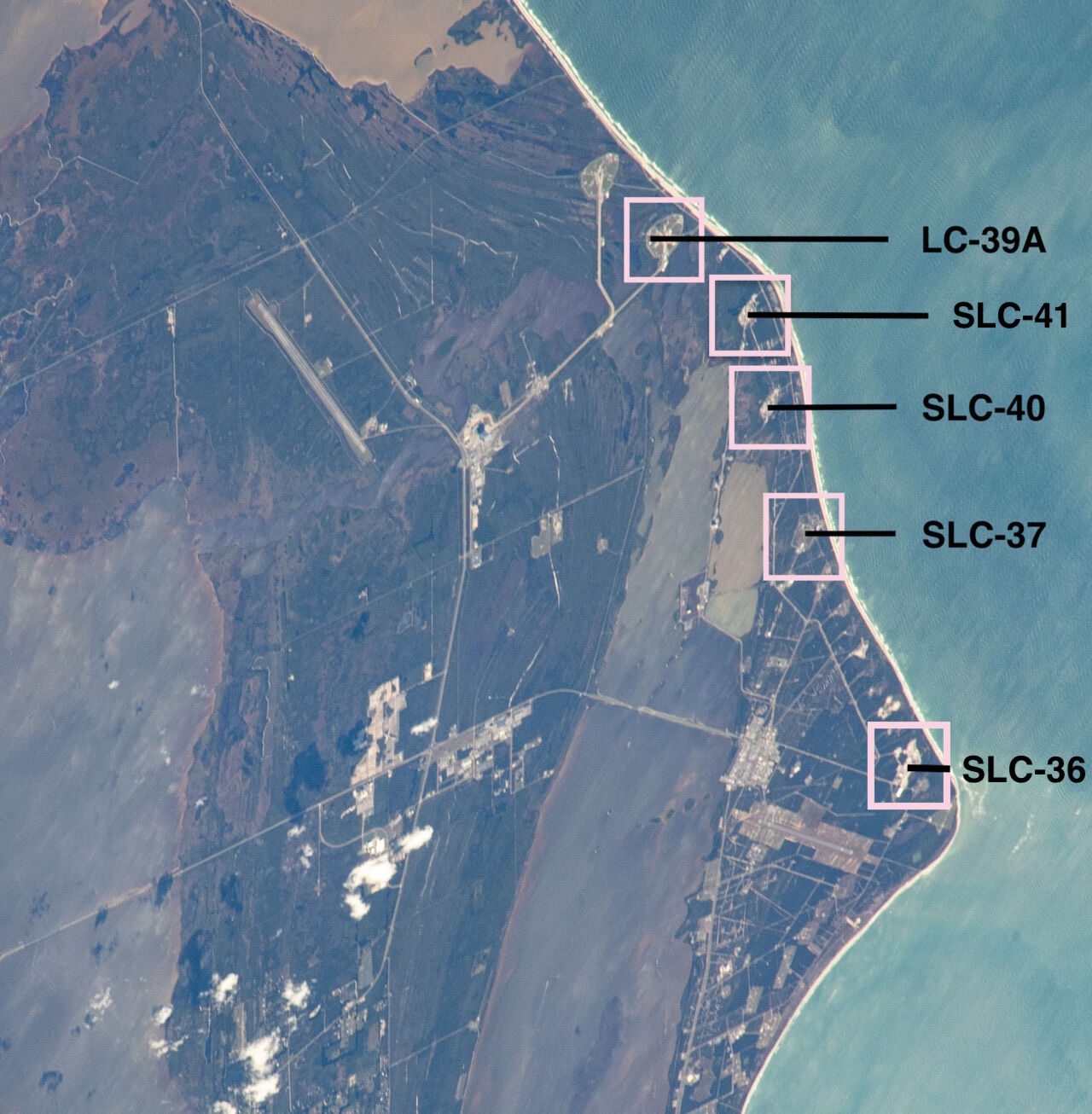

Construction crews are outfitting a second Starship launch tower at Starbase, called Pad B, that may also come online before the end of this year. A few miles north of SLC-37, SpaceX has built another Starship tower at Launch Complex 39A, a historic site on NASA property at Kennedy Space Center. Significant work remains ahead at LC-39A to install a new launch mount, finish digging a flame trench, and install all the tanks and plumbing necessary to store and load super-cold propellants into the rocket. The most recent official schedule from SpaceX suggests a first Starship launch from LC-39A could happen before the end of the year, but it’s probably a year or more away.

The Air Force’s draft Environmental Impact Statement includes this map showing SpaceX’s site plan for SLC-37. Credit: Department of the Air Force

Similar to the approach SpaceX is taking at SLC-37, a document released last year indicates the Starship team plans to construct a separate catch tower near the Starship launch tower at LC-39A. If built, these catch towers could simplify Starship operations as the flight rate ramps up, allowing SpaceX to catch a returning rocket at one location while stacking Starships for launch with the chopstick arms on nearby integration towers.

With SpaceX’s growing footprint in Texas and Florida, the company has built, is building, or revealed plans to build at least five Starship launch towers. This number is likely to grow in the coming years as Musk aims to eventually launch and land multiple Starships per day. This will be a gradual ramp-up as SpaceX works through Starship design issues, grows factory capacity, and brings new launch pads online.

Last month, the Federal Aviation Administration—which oversees environmental reviews for launch sites that aren’t on military property—approved SpaceX’s request to launch Starships as many as 25 times per year from Starbase, Texas. The previous limit was five, but the number will likely go up from here. Coming into 2025, SpaceX sought to launch as many as 25 Starships this year, but failures on three of the rockets’ most recent test flights have slowed development, and this goal is no longer achievable.

That’s a lot of launches

Meanwhile, in Florida, the FAA’s environmental review for LC-39A is assessing the impact of launching Starships up to 44 times per year from Kennedy Space Center. At nearby Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, the Air Force is evaluating SpaceX’s proposal for up to 76 Starship flights per year from SLC-37. The scope of each review also includes environmental assessments for Super Heavy and Starship landings within the perimeters of each launch complex.

While the draft EIS for SLC-37 is now public, the FAA hasn’t yet released a similar document for SpaceX’s planned expansion and Starship launch operations at LC-39A, also home to a launch pad used for Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy flights.

SpaceX will continue launching its workhorse Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy rockets as Starship launch pads heat up with more test flights. Within a few years, SpaceX could have as many as nine active launch pads spread across three states. The company’s most optimistic vision for Starship would require many more, potentially including offshore launch and landing sites.

At Vandenberg Space Force Base in California, SpaceX has leased the former West Coast launch pad for United Launch Alliance’s Delta IV rocket. SpaceX will prepare this launch pad, known as SLC-6, for Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy launches starting as soon as next year, augmenting the capacity of the company’s existing Vandenberg launch pad, which is only configured for Falcon 9s. Like the demolition at SLC-37 in Florida, the work to prepare SLC-6 will include the razing of unnecessary towers and structures left over from the Delta IV (and the Space Shuttle) program.

SpaceX has not yet announced any plans to launch Starships from the California spaceport.

SpaceX launches Falcon 9 rockets from Pad 39A at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center and from Pad 40 at Cape Canaveral Space Force Station. The company plans to develop Starship launch infrastructure at Pad 39A and Pad 37. United Launch Alliance flies Vulcan and Atlas V rockets from Pad 41, and Blue Origin has based its New Glenn rocket at Pad 36. Credit: NASA (labels by Ars Technica)

The expansion of SpaceX’s launch facilities comes as most of its closest competitors limit themselves to just one or two launch pads. ULA has reduced its footprint from seven launch pads to two as a cost-cutting measure. Blue Origin, Jeff Bezos’ space company, operates a single launch pad at Cape Canaveral, although it has unannounced plans to open a launch facility at Vandenberg. Rocket Lab has three operational launch pads in New Zealand and Virginia for the light-class Electron rocket and will soon have a fourth in for the medium-lift Neutron launcher.

These were the top four companies in Ars’ most recent annual power ranking of US launch providers.

Two of these competitors, ULA and Blue Origin, complained last year that SpaceX’s target of launching as many as 120 Starships per year from Florida’s Space Coast could force them to clear their launch pads for safety reasons. The Space Force is responsible for ensuring all personnel remain outside of danger areas during testing and launch operations.

It could become quite busy at Cape Canaveral. Military officials forecast that launch providers not named SpaceX could fly more than 110 launches per year. The Air Force acknowledged in the draft EIS that SpaceX’s plans for up to 76 launches and 152 landings (76 Starships and 76 Super Heavy boosters) per year at SLC-37 “could result in planning constraints for other range user operations.” This doesn’t take into account the FAA’s pending approval for up to 44 Starship flights per year from LC-39A.

But the report suggests SpaceX’s plans to launch from SLC-37 won’t require the evacuation of ULA and Blue Origin’s launch pads. While the report doesn’t mention the specific impact of Starship launches on ULA and Blue Origin, the Air Force wrote that work could continue on SpaceX’s own Falcon 9 launch pad at SLC-40 during a Starship launch at SLC-37. Because SLC-40 is closer to SLC-37 than ULA and Blue Origin’s pads, this finding seems to imply workers could remain at those launch sites.

The Air Force’s environmental report also doesn’t mention possible impacts of Starship launches from NASA property on nearby workers. It also doesn’t include any discussion of how Starship launches from SLC-37 might affect workers’ access to other facilities, such as offices and hangars, closer to the launch pad.

The bottom line of this section of the Air Force’s environmental report concluded that Starship flights from SLC-37 “should have no significant impact” on “ongoing and future activities” at the spaceport.

Shipping Starships

While SpaceX builds out its Starship launch pads on the Florida coast, the company is also constructing a Starship integration building a few miles away at Kennedy Space Center. This structure, called Gigabay, will be located next to an existing SpaceX building used for Falcon 9 processing and launch control.

The sprawling Gigabay will stand 380 feet tall and provide approximately 46.5 million cubic feet of interior processing space with 815,000 square feet of workspace, according to SpaceX. The company says this building should be operational by the end of 2026. SpaceX is also planning a co-located Starship manufacturing facility, similar to the Starfactory building recently completed at Starbase, Texas.

Until this factory is up and running, SpaceX plans to transport Starships and Super Heavy boosters horizontally via barges from South Texas to Cape Canaveral.

Stephen Clark is a space reporter at Ars Technica, covering private space companies and the world’s space agencies. Stephen writes about the nexus of technology, science, policy, and business on and off the planet.