Needs a Super Administrator

“I was very disappointed, especially because it was so close to confirmation.”

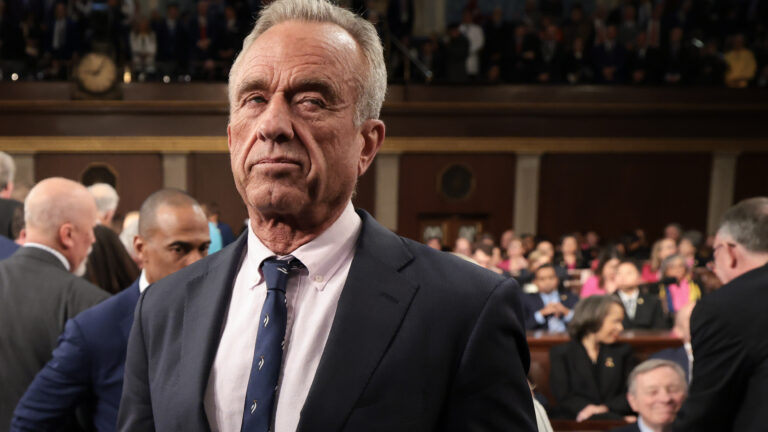

Jared Isaacman speaks at the Spacepower Conference in Orlando, Florida. Credit: John Kraus

Nearly two weeks have passed since Jared Isaacman received a fateful, brief phone call from two officials in President Trump’s Office of Personnel Management. In those few seconds, the trajectory of his life over the next three and a half years changed dramatically.

The president, the callers said, wanted to go in a different direction for NASA’s administrator. At the time, Isaacman was within days of a final vote on the floor of the US Senate and assured of bipartisan support. He had run the gauntlet of six months of vetting, interviews, and a committee hearing. He expected to be sworn in within a week. And then, it was all gone.

“I was very disappointed, especially because it was so close to confirmation and I think we had a good plan to implement,” Isaacman told Ars on Wednesday.

Isaacman’s nomination was pulled for political reasons. As SpaceX founder and one-time President Trump confidant Elon Musk made his exit from the White House, key officials who felt trampled on by Musk took their revenge. They knifed a political appointment, Isaacman, who shared Musk’s passion for extending humanity’s reach to Mars. The dismissal was part of a chain of events that ultimately led to a break in the relationship between Trump and Musk, igniting a war of words.

When I spoke with Isaacman this week, I didn’t want to rehash the political melee. I preferred to talk about his plan. After all, he had six months to look under the hood of NASA, identify the problems that were holding the space agency back, and release its potential in this new era of spaceflight.

A man with a plan

“It shouldn’t be a surprise, the organizational structure is very heavy with management and leadership,” Isaacman said. “Lots of senior leadership with long meetings, who have their deputies, who have their chiefs of staff, who have deputy chiefs of staff and associate deputies. It is not just a NASA problem; across government, there are principal, deputy, assistant-to-the-deputy roles. It makes it very hard to have a culture of ownership and urgent decision-making.”

Isaacman said his plan, a blueprint of more than 100 pages detailing various actions to modernize NASA and make it more efficient, would have started with the bureaucracy. “It was going to be hard to get the big, exciting stuff done without a reorganization, a rebuild, including cultural rebuilding, and an aggressive, hungry, mission-first culture,” he said.

One of his first steps would have been to attempt to accelerate the timeline for the Artemis II mission, which is scheduled to fly four astronauts around the Moon in April 2026. He planned to bring in “strike” teams of engineers to help move Artemis and other programs forward. Isaacman wanted to see the Artemis II vehicle on the pad later this summer, with the goal of launching in December of this year, echoing the historic launch of Apollo 8 in December 1968.

Isaacman also sought to reverse the space agency’s decision to cut utilization of the International Space Station due to budget issues.

“Instead of the current thinking, three crew members every eight months to manage the budget, I wanted to go seven crew members every four months,” he said. “I was even going to pay for one of the missions, if need be, to just get more people up there, more cracks at science, and try and figure out the orbital economy, or else life will be very hard on the commercial LEO destinations.”

As part of this, he would have pushed for certification of SpaceX’s Dragon spacecraft to carry seven astronauts—which was in the vehicle’s baseline design—instead of the current four. This would have allowed NASA to fly more professional astronauts, but also payload specialists like the agency used to do during the Space Shuttle program. Essentially, NASA experts of certain experiments would fly and conduct their own research.

“I wanted to bring back the Payload Specialist program and open it up to the NASA workforce,” he said. “Because things are pretty difficult right now, and I wanted to get people excited and reward the best.”

He also planned to seek goodwill by donating his salary as administrator to Space Camp at the US Space & Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama, for scholarships to inspire the next generation of explorers.

Nuclear spaceships

Isaacman’s signature issue was going to be a full-bore push into nuclear electric propulsion, which he views as essential for the sustainable exploration of the Solar System by humans. Nuclear electric propulsion converts heat from a fission reactor to electrical power, like a power plant on Earth, and then uses this energy to produce thrust by accelerating an ionized propellant, such as xenon. Nuclear propulsion requires significantly less fuel than chemical propulsion, and it opens up more launch windows to Mars and other destinations.

“We would have gone right to a 100-kilowatt test vehicle that we would send somewhere inspiring with some great cameras,” he said. “Then we are going right to megawatt class, inside of four years, something you could dock a human-rated spaceship to, or drag a telescope to a Lagrange point and then return, big stuff like that. The goal was to get America underway in space on nuclear power.”

Another key element of this plan is that it would give some of NASA’s field centers, including Marshall Space Flight Center, important work to do after the cancellation of the Space Launch System rocket.

“Pivoting to nuclear spaceships, in my mind, was just the right thing to do for the SLS states, even if it’s not the right locations or the right people. There is a lot of dollars there that those states don’t want to let go of,” he said. “When you speak to those senators, if you give them another kind of bar to grab onto, they can get excited about what comes next. And imagine an SLS-caliber budget going into building, literally, nuclear orbiters that could do all sorts of things. That’s directionally correct, right?”

What direction NASA takes now is unclear, but the loss of Isaacman is acute. The agency’s acting administrator, Janet Petro, is largely taking direction from the White House Office of Management and Budget and has no independence. A confirmed administrator is now months away. The lights at the historic space agency get a little dimmer each day as a result.

Considering politics

As for what he plans to do now that he suddenly has time on his hands—Isaacman stepped down as chief executive of Shift4, the financial payments company he founded, to become NASA administrator—Isaacman is weighing his options.

“I’m sure a lot of supporters in the space community would love to hear me say that I’m done with politics, but I’m not sure that’s the case,” he said. “I want to serve our country, give back, and make a difference. I don’t know what, but I will find something.”

What his role in politics would be, Isaacman, who has described himself as a moderate, Republican-leaning voter, is unsure. However, he wants to help bridge a nation that is riven by partisan politics. “I think if you don’t have more moderates and better communicators try to pull us closer together, we’re just going to keep moving farther apart,” he said. “And that just doesn’t seem like it’s in any way good for the country.”

Eric Berger is the senior space editor at Ars Technica, covering everything from astronomy to private space to NASA policy, and author of two books: Liftoff, about the rise of SpaceX; and Reentry, on the development of the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon. A certified meteorologist, Eric lives in Houston.