A little less than four years from now, a killer asteroid will narrowly fly past planet Earth. This will be a celestial event visible around the world—for a few weeks, Apophis will shine among the brightest objects in the night sky.

The near miss by the large Apophis asteroid in April 2029 offers NASA a golden—and exceedingly rare—opportunity to observe such an object like this up close. Critically, the interaction between Apophis and Earth’s gravitational pull will offer scientists an unprecedented chance to study the interior of an asteroid.

This is fascinating for planetary science, but it also has serious implications for planetary defense. In the future, were such an asteroid on course to strike Earth, an effective plan to deflect it would depend on knowing what the interior looks like.

“This is a remarkable opportunity,” said Bobby Braun, who leads space exploration for the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, in an interview. “From a probability standpoint, there’s not going to be another chance to study a killer asteroid like this for thousands of years. Sooner or later, we’re going to need this knowledge.”

But we may not get it.

NASA has some options for tracking Apophis during its flyby. However, the most promising of these, a mission named OSIRIS-Apex that breathes new life into an old spacecraft that otherwise would drift into oblivion, is slated for cancellation by the Trump White House’s budget for fiscal year 2026.

Other choices, including dragging dual space probes out of storage, the Janus spacecraft, and other concepts that were submitted to NASA a year ago as part of a call for ideas, have already been rejected or simply left on the table. As a result, NASA currently has no plans to study what will be the most important asteroid encounter since the formation of the space agency.

“The world is watching,” said Richard Binzel, an asteroid expert at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. “NASA needs to step up and do their job.”

But will they?

A short history of planetary defense

For decades, nearly every public survey asking what NASA should work on has rated planetary defense at or near the very top of the space agency’s priorities. Yet for a long time, no part of NASA actually focused on finding killer asteroids or developing the technology to deflect them.

In authorization bills dating back to 2005, Congress began mandating that NASA “detect, track, catalog, and characterize” near-Earth objects that were 140 meters in diameter or larger. Congress established a goal of finding 90 percent of these by the year 2020. (We’ve blown past that deadline, obviously.)

NASA had been informally studying asteroids and comets for decades but did not focus on planetary defense until 2016, when the space agency established the Planetary Defense Coordination Office. In the decade since, NASA has made some progress, identifying more than 26,000 near-Earth objects, which are defined as asteroids and comets that come within 30 million miles of our planet’s orbit.

Moreover, NASA has finally funded a space mission designed specifically to look for near-Earth threats, NEO Surveyor, a space telescope with the goal of “finding asteroids before they find us.” The $1.2 billion mission is due to launch no earlier than September 2027.

NASA also funded the DART mission, which launched in 2021 and impacted a 160-meter asteroid named Dimorphous a year later to demonstrate the ability to make a minor deflection.

But in a report published this week, NASA’s Office of Inspector General found that despite these advances, the space agency’s approach to planetary defense still faces some significant challenges. These include a lack of resources, a need for better strategic planning, and competition with NASA’s more established science programs for limited funding.

A comprehensive plan to address planetary defense must include two elements, said Ed Lu, a former NASA astronaut who co-founded the B612 Foundation to protect Earth from asteroid impacts.

The first of these is the finding and detection of asteroid threats. That is being addressed both by the forthcoming NEO Surveyor and the recently completed Vera C. Rubin Observatory, which is likely to find thousands of new near-Earth threats. The challenge in the coming years will be processing all of this data, calculating orbits, and identifying threats. Lu said NASA must do a better job of being transparent in how it makes these calculations.

The second thing Lu urged NASA to do is develop a follow-up mission to DART. It was successful, he said, but DART was just an initial demonstration. Such a capability needs to be tested against a larger asteroid with different properties.

An asteroid that might look a lot like Apophis.

About Apophis

Astronomers using a telescope in Arizona found Apophis in 2004, and they were evidently fans of the television series Stargate SG-1, in which a primary villain who threatens civilization on Earth is named Apophis.

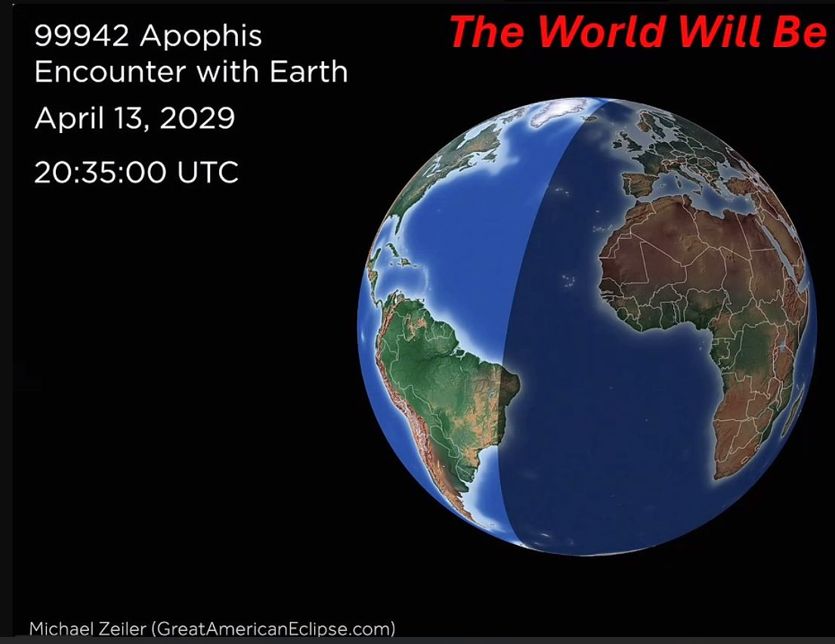

Because of its orbit, Apophis comes near Earth about every eight years. It is fairly large, about 370 meters across. This is not big enough to wipe out civilization on Earth, but it would cause devastating consequences across a large region, imparting about 300 times as much impact force on the planet as the Tunguska event in 1908, over Siberia. It will miss Earth by about 31,600 km (19,600 miles) on April 13, 2029.

“We like to say that’s because nature has a sense of humor,” said Binzel, the MIT asteroid scientist, of this date.

Astronomers estimate that an asteroid this large comes this close to Earth only about once every 7,500 years. It also appears to be a stony, non-metallic type of asteroid known as an ordinary chondrite. This is the most common type of asteroid in the Solar System.

Areas of the planet that will be able to see Apophis at its closest approach to Earth in April 2029.

Credit: Rick Binzel

Areas of the planet that will be able to see Apophis at its closest approach to Earth in April 2029. Credit: Rick Binzel

All of this is rather convenient for scientists hoping to understand more about potential asteroids that might pose a serious threat to the planet.

The real cherry on top with the forthcoming encounter is that Apophis will be perturbed by Earth’s gravitational pull.

“Nature is handing us an incredibly rare experiment where the Earth’s gravity is going to tug and stretch this asteroid,” Binzel said. “By seeing how the asteroid responds, we’ll know how it is put together, and knowing how an asteroid is put together is maybe the most important information we could have if humanity ever faces an asteroid threat.”

In nearly seven decades of spaceflight, humans have only ever probed the interior of three celestial bodies: the Earth, the Moon, and Mars. We’re now being offered the opportunity to probe a fourth, right on our doorstep.

But time is ticking.

Chasing Apophis

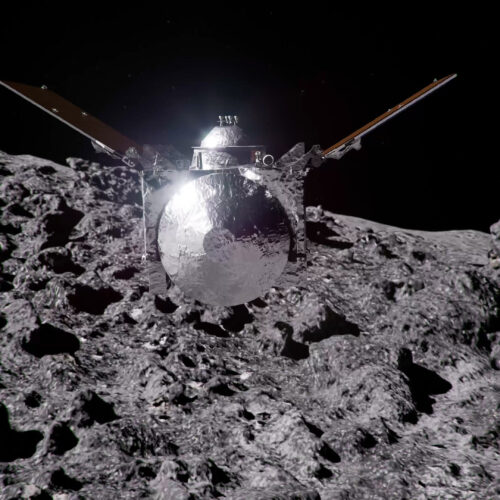

On paper, at least, NASA has a plan to rendezvous with Apophis. About three years ago, after a senior-level review, NASA extended the mission of the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft to rendezvous with Apophis.

As you may recall, this oddly named spacecraft collected a sample from another asteroid, Bennu, in October 2020. Afterward, a small return capsule departed from the main spacecraft and made its way back to Earth. Since then, an $800 million spacecraft specifically designed to fly near and touch an asteroid has been chilling in space.

So it made sense when NASA decided to fire up the mission, newly rechristened OSIRIS-Apex, and re-vector it toward Apophis. It has been happily flying toward such a rendezvous for a few years. The plan was for Apex to catch up to Apophis shortly after its encounter with Earth and study it for about 18 months.

“The most cost-efficient thing you can do in spaceflight is continue with a heathy spacecraft that is already operating in space,” Binzel said.

And that was the plan until the Trump administration released its budget proposal for fiscal year 2026. In its detailed budget information, the White House provided no real rationale for the cancellation, simply stating, “Operating missions that have completed their prime missions (New Horizons and Juno) and the follow-on mission to OSIRIX-REx, OSIRIS-Apophis Explorer, are eliminated.”

It’s unclear how much of a savings this resulted in. However, Apex is a pittance in NASA’s overall budget. The operating funds to keep the mission alive in 2024, for example, were $14.5 million. Annual costs would be similar through the end of the decade. This is less than one-thousandth of NASA’s budget, by the way.

“Apex is already on its way to reach Apophis, and to turn it off would be an incredible waste of resources,” Binzel said.

Congress, of course, ultimately sets the budget. It will have the final say. But it’s clear that NASA’s primary mission to study a once-in-a-lifetime asteroid is at serious risk.

So what are the alternatives?

Going international and into the private sector

NASA was not the only space agency targeting Apophis. Nancy Chabot, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, has been closely tracking other approaches.

The European Space Agency has proposed a mission named Ramses to rendezvous with the asteroid and accompany it as it flies by Earth. This mission would be valuable, conducting a thorough before-and-after survey of the asteroid’s shape, surface, orbit, rotation, and orientation.

It would need to launch by April 2028. Recognizing this short deadline, the space agency has directed European scientists and engineers to begin preliminary work on the mission. But a final decision to proceed and commit to the mission will not be made before the space agency’s ministerial meeting in November.

Artist’s impression of ESA’s Rapid Apophis Mission for Space Safety (Ramses). Credit: ESA

This is no sure thing. For example, Chabot said, in 2016, the Asteroid Impact Mission was expected to advance before European ministers decided not to fund it. It is also not certain that the Ramses mission would be ready to fly in less than three years, a short timeline for planetary science missions.

Japan’s space agency, JAXA, is also planning an asteroid mission named Destiny+ that has as its primary goal flying to an asteroid named 3200 Phaeton. The mission has been delayed multiple times, so its launch is now being timed to permit a single flyby of Apophis in February 2029 on the way to its destination. While this mission is designed to deliver quality science, a flyby mission provides limited data. It is also unclear how close Destiny+ will actually get to Apophis, Chabot said.

There are also myriad other concepts, commercial and otherwise, to characterize Apophis before, during, and after its encounter with Earth. Ideally, scientists say, a mission would fly to the asteroid before April 2029 and scatter seismometers on the surface to collect data.

But all of this would require significant funding. If not from NASA, who? The uncertain future of NASA’s support for Apex has led some scientists to think about philanthropy.

For example, NASA’s Janus spacecraft have been mothballed for a couple of years, but they could be used for observational purposes if they had—say—a Falcon 9 to launch them at the appropriate time.

A new, private reconnaissance mission could probably be developed for $250 million or less, industry officials told Ars. There is still enough time, barely, for a private group to work with scientists to develop instrumentation that could be added to an off-the-shelf spacecraft bus to get out to Apophis before its Earth encounter.

Private astronaut Jared Isaacman, who has recently indicated a willingness to support robotic exploration in strategic circumstances, confirmed to Ars that several people have reached out about his interest in financially supporting an Apophis mission. “I would say that I’m in info-gathering mode and not really rushing into anything,” Isaacman said.

The problem is that, at this very moment, Apophis is rushing this way.

Eric Berger is the senior space editor at Ars Technica, covering everything from astronomy to private space to NASA policy, and author of two books: Liftoff, about the rise of SpaceX; and Reentry, on the development of the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon. A certified meteorologist, Eric lives in Houston.