“We think that’s a really important mission, and something that we can do.”

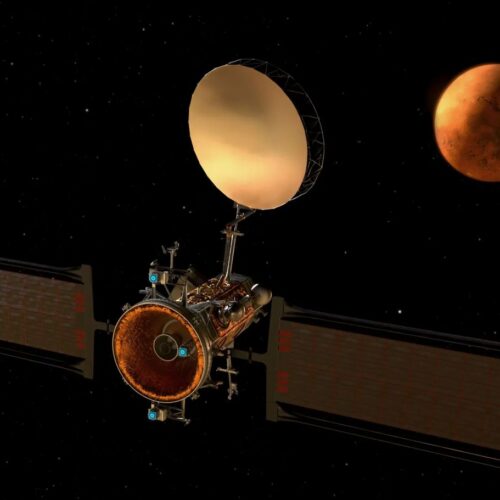

This is Blue Origin’s design for a Mars Telecommunications Orbiter. Credit: Blue Origin

A consequential debate that has been simmering behind closed doors at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC, must soon come to a head. It concerns the selection of the next spacecraft the agency will fly to Mars, and it could set the tone for the next decade of exploration of the red planet.

What everyone agrees on is that NASA needs a new spacecraft capable of relaying communications from Mars to Earth. This issue has become especially acute with the recent loss of NASA’s MAVEN spacecraft. NASA’s best communications relay remains the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, which has now been there for 20 years.

Congress cared enough about this issue to add $700 million in funding for a “Mars Telecommunications Orbiter” in the supplemental funding for NASA provided by the “One Big Beautiful Bill” passed by the US Congress last year.

That’s a lot of money purely for a telecom orbiter

However, this legislation, led by Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, raised a couple of key questions. The first is the specific wording of the bill, authored by a key Cruz staff member, Maddie Davis. It specified that the orbiter must be selected from among US companies that “received funding from the Administration in fiscal year 2024 or 2025 for commercial design studies for Mars Sample Return; and proposed a separate, independently launched Mars telecommunication orbiter supporting an end-to-end Mars sample return mission.”

The reference to “commercial design studies” referred to companies that proposed faster and more affordable missions to return samples from Mars, selected in 2024. Several observers told Ars the language included here appeared designed to favor Rocket Lab and its proposal for a telecommunications orbiter.

The other curious thing about the Cruz language is that it specified $700 million for the spacecraft and its launch, which seems like overkill.

“$500 million is plenty for a communications payload, satellite bus, and launch,” one knowledgeable industry official told Ars. “I actually think those functions could be provided for well below $500 million.”

NASA’s new administrator, Jared Isaacman, has been dealing with a lot of issues since being sworn in a little more than a month ago, including the impending launch of the Artemis II mission, now scheduled for no earlier than February 8. However, time is running out to deal with the Mars Telecommunications Orbiter.

That’s because the legislation requires funding for the spacecraft to be obligated “not later than fiscal year 2026,” which ends on September 30, 2026. The mission would also need to be awarded soon to allow a spacecraft to launch in late 2028, the earliest feasible launch window to Mars. It’s notable that NASA has no spacecraft presently scheduled to launch to Mars in the 2026 window, so the Mars Telecommunications Orbiter is potentially the only vehicle the space agency would launch to Mars during the second Trump administration, which wants to make its mark on the red planet.

All of this adds fuel to the internal debate at NASA about the design and scope of the competition to award a Mars Telecommunications Orbiter.

To science or not to science?

Given the available funding, a number of people within the agency are pressing to include scientific instruments on the orbiter. Three good instruments could be added for about $200 million, a science official said. Ideas include everything from a high-resolution camera (again, badly needed since the best camera at Mars is on the 20-year-old Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter), a space weather payload, a magnetometer to understand Mars’ remnant magnetic field, or a spectrometer to look for near-surface water ice. It’s possible that some instruments from the canceled Mars Ice Mapper mission could also be repurposed or even a small lander included.

“To me, it seems like an easy decision,” said Casey Dreier, chief of space policy at The Planetary Society. Adding a package of science instruments to a mission already headed to Mars aligns with NASA’s goal of maximizing science and exploring the potential of rapidly developed, low-cost science experiments, he added. “This project is already going to Mars, and science would add real value.”

However, some leaders within NASA see the language in the Cruz legislation as spelling out a telecommunications orbiter only and believe it would be difficult, if not impossible, to run a procurement competition between now and September 30th for anything beyond a straightforward communications orbiter.

In a statement provided to Ars by a NASA spokesperson, the agency said that is what it intends to do.

“NASA will procure a high-performance Mars telecommunications orbiter that will provide robust, continuous communications for Mars missions,” a spokesperson said. “NASA looks forward to collaborating with our commercial partners to advance deep space communications and navigation capabilities, strengthening US leadership in Mars infrastructure and the commercial space sector.”

Big decisions loom

Even so, sources said Isaacman has yet to decide whether the orbiter should include scientific instruments. NASA could also tap into other funding in its fiscal year 2026 budget, which included $110 million for unspecified “Mars Future Missions,” as well as a large wedge of funding that could potentially be used to support a Mars commercial payload delivery program.

The range of options before NASA, therefore, includes asking industry for a single telecom orbiter from one company, asking for a telecom orbiter with the capability to add a couple of instruments, or creating competition by asking for multiple orbiters and capabilities by tapping into the $700 million in the Cruz bill but then augmenting this with other Mars funding.

One indication that this process has been muddied within NASA came a week ago, when the space agency briefly posted a “Justification for Other Than Full and Open Competition, Extension” notice on a government website. It stated that the agency “will only conduct a competition among vendors that satisfy the statutory qualifications.” The notice also listed the companies eligible to bid based on the Cruz language: Blue Origin, L3Harris, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, Rocket Lab, SpaceX, Quantum Space, and Whittinghill Aerospace.

This justification, known in industry parlance as a JOFOC, was then taken down almost immediately. A user on the social media site X captured a screenshot before it was removed, however.

Sources suggested that the brief appearance of this document indicates that NASA is concerned about running a competition in the coming months and recognizes that any protests could delay the awarding of funds beyond September 30, when they would return to the treasury. A JOFOC would limit companies’ ability to protest and delay awards.

For the commercial space companies, this will be a consequential decision. Lockheed Martin has a long and storied history of providing quality spacecraft in orbit around Mars and will seek to protect its turf. But new space entrants Rocket Lab, Blue Origin (with a design based on its Blue Ring spacecraft), and SpaceX (likely using a modified Starlink V3 satellite) would all like to break into the planetary spacecraft competition and have been working on their spacecraft. As a result, they might have a better chance of making a 2028 Mars window.

“We’re pushing hard on the MTO,” Rocket Lab CEO Pete Beck told Ars in November. “The reality is that if you’re going to do anything on Mars, whether it’s scientific or human, you’ve got to have the comms there. It’s just basic infrastructure you’ve got to have there first. It’s all very well to do all the sexy stuff and put some humans in a can and send them off to Mars. That’s great. But everybody expects the communication just to be there, and you’ve got to put the foundations in first. So we think that’s a really important mission, and something that we can do, and something we can contribute to the first humans landing on Mars.”

Eric Berger is the senior space editor at Ars Technica, covering everything from astronomy to private space to NASA policy, and author of two books: Liftoff, about the rise of SpaceX; and Reentry, on the development of the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon. A certified meteorologist, Eric lives in Houston.