Half of a year of data shows that the solar boom is not slowing down.

On Tuesday, the US Energy Information Agency released its latest data on how the US generated electricity during the first six months of 2025. The data suggests the notable surge in power use is flattening out a bit compared to earlier in the year, with the growth in coal use falling along with it. And despite the best efforts of the Trump Administration, the boom in solar power continues, with solar looking poised to pass hydroelectric before the year is out.

Growing, but moderating

For the last few decades, the US has largely seen its use of electricity remain flat. That’s changed over the last year or so, with energy use ramping up, likely due in part to increased data center use. Earlier in the year, data indicated that demand for electricity was up roughly five percent year-over-year. But that seems to be tailing off over the course of the spring, leaving total electricity demand up by three percent for the January-through-June period.

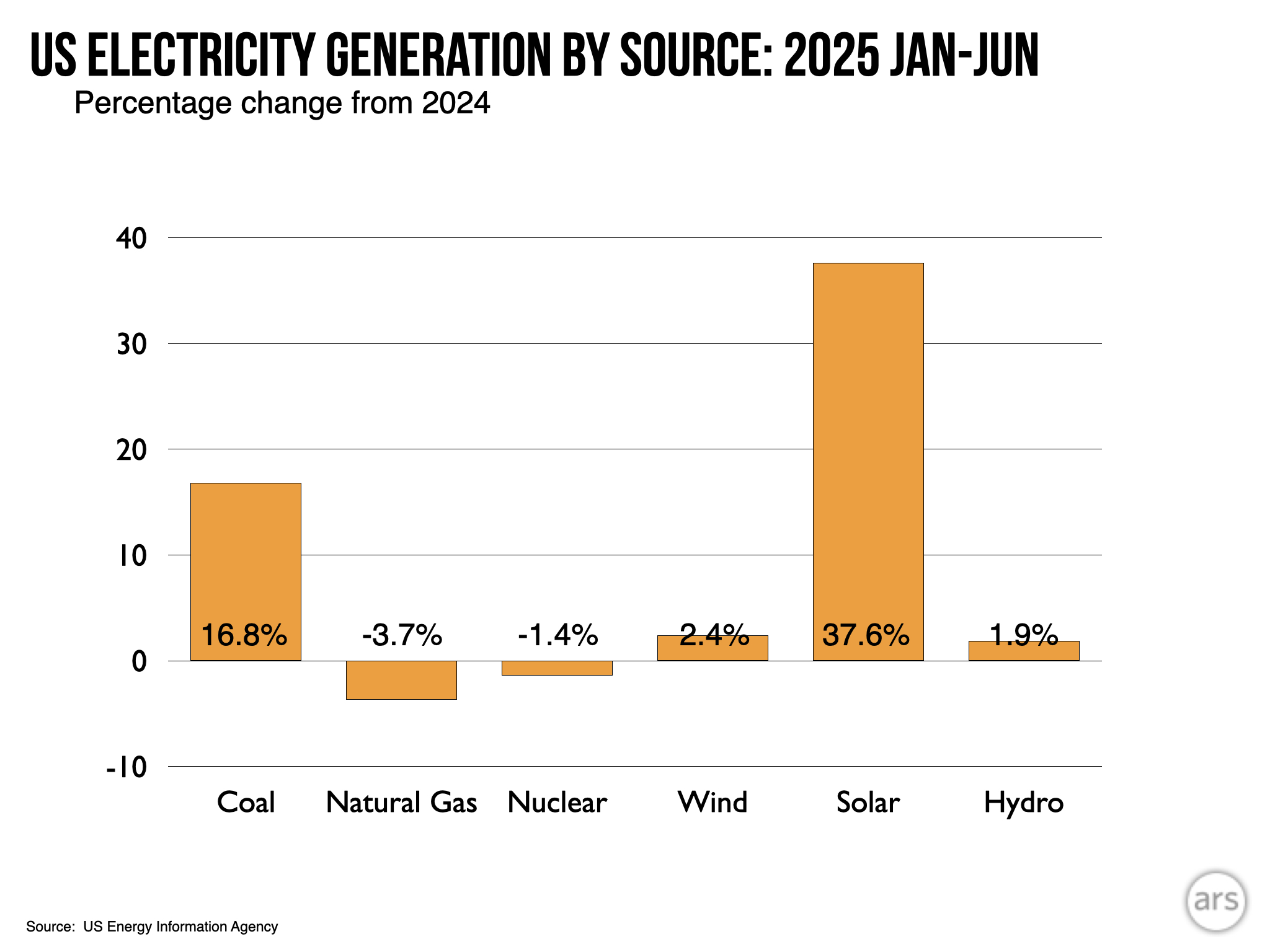

The somewhat lower demand has had a positive effect on coal use. Earlier this year, coal was up by about 20 percent compared to the same period the year before. Now, it’s only up by a bit under 17 percent. That’s still terrible given coal’s environmental and health impacts, not to mention its cost. But it’s not as bad as it has been, and it could have been even better had the Trump Administration not forced a coal plant that was slated for closure to stay open.

The other big percentage change is in solar power, which has continued its sharp rise, with a gain of nearly 40 percent. Solar is expected to account for the majority of new generating capacity set to be installed this year.

Compared to a year earlier, the only big changes are coal and solar. Credit: John Timmer

In terms of actual Terawatt-hours produced, the increase in solar power (about 40 TW-hr) was close to offsetting the increase in coal generation (50 TW-hr). The other big change was in natural gas, which dropped by 32 TW-hr compared to the same period the year before. But because natural gas is the largest single source of electrical generation in the US, that amounts to just a 3.7 percent change year-over-year.

Where does that leave the grid? Despite the slight decline, natural gas continues its dominance, fueling 39 percent of the power placed on the grid during the first half of 2025. Nuclear follows at 18 percent, with coal at 17. The renewables in order are wind (12 percent), solar (7 percent), and hydro (6 percent). (Numbers may not add up to 100 percent due to rounding and the fact that a number of energy sources are at under one percent and not included here.)

Renewables booming

Those last numbers could be significant, as hydroelectric generation tends to peak in the spring during the snow melt. In contrast, with additional solar plants coming online over the course of the year, there’s a good chance that in 2025, grid-scale solar will end up producing more electricity than hydroelectric plants for the first time. That’s especially notable because hydroelectric generation is largely the same as it was the year prior, indicating that it is being passed due to the growth in solar alone.

Collectively, the three renewables have provided 25 percent of the US’s electricity over the first half of the year. That means renewables are now second only to natural gas. If you add in nuclear power to get a sense of the emissions-free generation, we’re now up to 43 percent of the electricity produced.

The one thing missing from this analysis is non-utility solar—the rooftop generation that is found on residential and commercial buildings, as well as some of the small-scale community solar. The EIA doesn’t directly track its production, partly because a lot of it is used where it’s produced and never ends up on the grid, instead showing up simply as lower demand. It does, however, estimate its production, with it rising by about 11 percent or five TW-hr year-over-year.

We also did a couple of additional analyses using these estimates under the assumption that 100 percent of this power didn’t end up on the grid and thus displaced demand. The five TW-hr change compares to an increase in consumption of about 62 TW-hr overall. That means demand would have risen by about seven percent more if this solar hadn’t been in production.

If we added the total small-scale solar generation to the total demand for the first half of 2025, none of the other sources of electricity saw their percentages change much—all of them dropped, but by less than a percentage point. But combining the small- and grid-scale solar into a single total shifted its production enough to cover nearly 9 percent of the total demand.

A hazy future

The striking thing about the first half of 2025 is that coal has played such a large role in meeting demand, despite the fact that it is the least efficient, most expensive way to generate electricity in the US unless you’re willing to build a brand-new nuclear plant. Natural gas is considerably cheaper (which is how it came to be the dominant fuel), so if the demand could be met by quickly bringing new gas capacity online, it probably would. Yet natural gas use is actually down, suggesting that a lot of the growth in renewables has simply displaced it.

For the rest of the year, the EIA expects that most of the newly installed capacity will be either solar or batteries, the latter of which will undoubtedly end up storing some of that solar. Those projects were already in the pipeline before Trump returned to office, so it’s unlikely that anything will change there unless the administration starts to try to block ongoing projects, as it has with offshore wind.

Looking further out, though, the situation becomes uncertain. The administration is planning to block any renewable projects on public lands, and Trump has made some of the same false statements about solar that he has about wind power. Eventually, the administration will face a choice between embracing its ideological commitment to fossil fuels and the reality that there aren’t alternatives that can scale as fast as solar right now. Rising demand without new capacity to feed it will increase the use of expensive, inefficient generators.

John is Ars Technica’s science editor. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Biochemistry from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in Molecular and Cell Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. When physically separated from his keyboard, he tends to seek out a bicycle, or a scenic location for communing with his hiking boots.