Over the course of 2025, electricity demand has gradually declined.

Worries about the US grid’s ability to handle the surge in demand due to data center growth have made headlines repeatedly over the course of 2025. And, early in the year, demand for electricity had surged by nearly 5 percent compared to the year prior, suggesting the grid might truly be facing a data center apocalypse. And that rise in demand had a very unfortunate effect: Coal use rose for the first time since its recent collapse began.

But since the first-quarter data was released, demand has steadily eroded. As of yesterday’s data release by the Energy Information Administration (EIA), which covers the first nine months of 2025, total electricity demand has risen by 2.3 percent. That slowdown means that most of the increased demand could have been met by the astonishing growth of solar power.

Better than feared

If you look over data on the first quarter of 2025, the numbers are pretty grim, with total demand rising by 4.8 percent compared to the same period in the year prior. While solar power continued its remarkable surge, growing by an astonishing 44 percent, it was only able to cover a third of the demand growth. As a result of that and a drop in natural gas usage, coal use grew by 23 percent.

Six months have made a big difference. Total electricity demand is rising, but at a far more moderate 2.3 percent, and, depending on how the weather drives heating demand, that number could be even lower by the end of the year. The growth of solar, in contrast, has only tailed off slightly—it’s still up by 36 percent year over year. As such, solar growth was enough to offset over 80 percent of the increased demand. (Though, as we’ll discuss below, solar’s use is probably directly undercutting natural gas.) We’re nearly at the point where solar is growing fast enough to completely offset a notable growth in demand.

Coal’s problems are significant. It kills people via airborne pollution, leaves behind a toxic ash, and emits a lot of carbon dioxide for each unit of energy produced. So any increase in coal use is bad news. But the increase in the first three-quarters of 2025 is down to 13 percent, and it had fallen further still in the latest month for which data is available (meaning that if you consider only September, coal was up just 7 percent compared to September 2024).

Solar has now passed hydro, and is likely to pass wind within the next two years. John TImmer

The other notable change is a drop in the use of natural gas. While natural gas use fell by just under 4 percent, its status as the largest single source of generation in the US means that even small changes have an oversized impact.

Small-scale solar, which includes things like residential and commercial rooftop installations, is also growing, albeit at a far slower pace: It was up by 11 percent compared to the year prior. A lot of it is consumed without ever reaching the grid, so it shows up in these numbers as reduced demand, rather than as a distinct generating source. Nevertheless, if you combine small- and grid-scale solar production, total solar in the US is poised to overtake wind power (it’s above 90 percent of wind’s production) after having already passed hydropower. It will take two years of similar growth for grid-scale solar to pass wind on its own, though, and by that point, wind and solar combined will produce more power than nuclear energy.

Carbon accounting

Despite the increase in coal use, wind and solar remain a larger source of electrons, although it’s close enough that a change before the end of the year remains possible (both coal and wind + solar are handling 17 percent of the total consumption). Wind covered 10 percent of demand, while utility-scale solar handled 7 percent. Add in hydropower, and the total generation by renewables is responsible for 23 percent of the US’s electricity production.

If you add in nuclear, then the US has reached a grid that is 40 percent emissions-free over the first nine months of 2025. That’s up only 1 percent compared to the same period the year prior. And because coal emits more carbon than natural gas, it’s likely the US will see a net increase in electricity-related emissions this year.

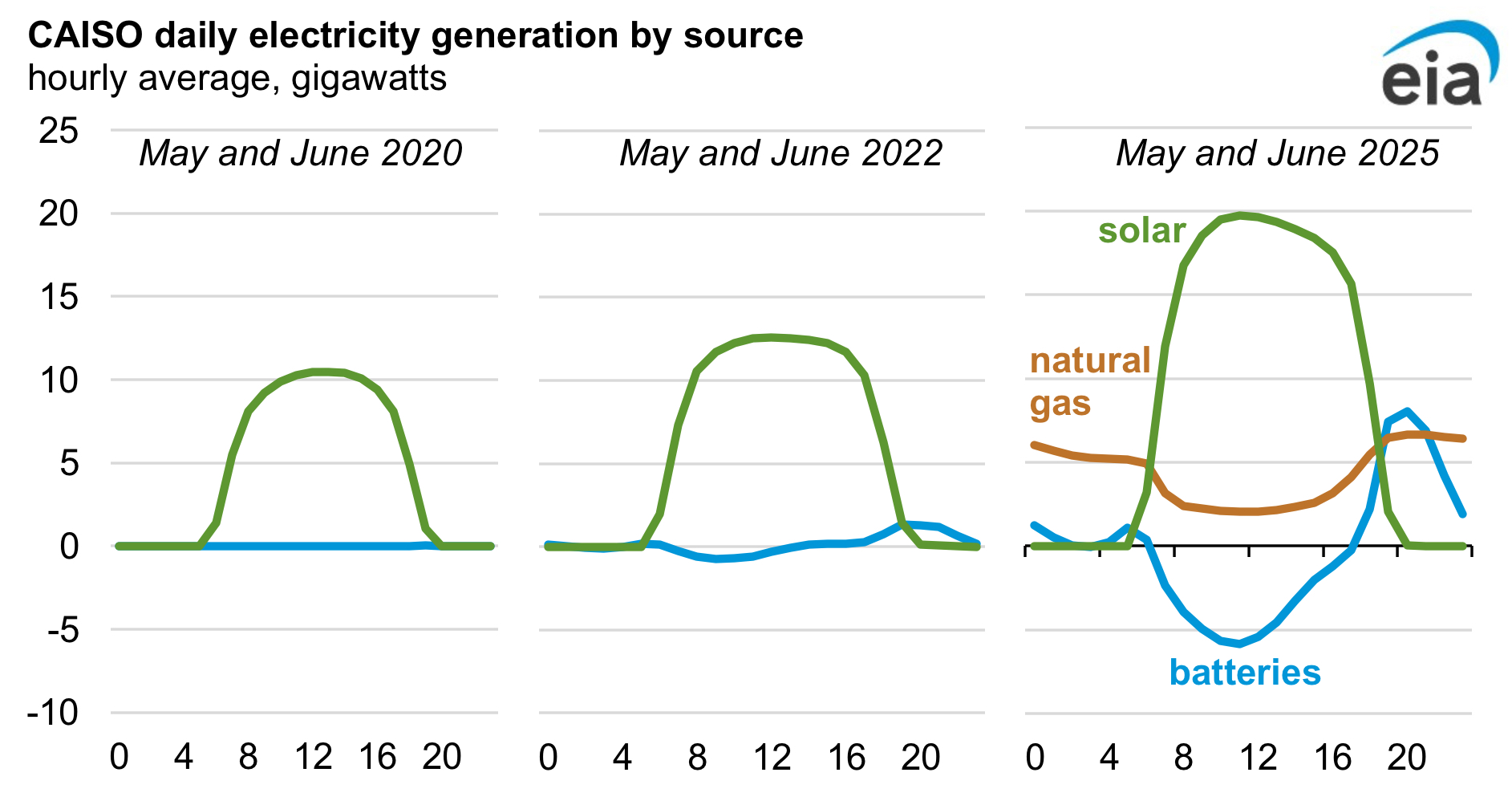

If you would like to have a reason to feel somewhat more optimistic, however, the EIA used the new data to release an analysis of the state of the grid in California, where the production from utility-scale solar has nearly doubled over the last five years, thanks in part to another 17 percent increase so far in 2024.

Through 2023, it was tough to discern any impact of that solar production on the rest of the grid, in part due to increased demand. But since then, natural gas use has dropped considerably (it’s down by 17 percent so far in 2025), placing it at risk of being displaced by solar as the largest source of electricity in California as early as next year. This displacement is happening even as California’s total consumption jumped by 8 percent so far in 2025 compared to the same period last year.

Massive solar growth plus batteries means less natural gas on California’s grid. Credit: US EIA

The massive growth in solar has also led to overproduction of power in the spring and autumn, when heating/cooling demands are lowest. That, in turn, has led to a surge in battery construction to absorb the cheap power and sell it back after the Sun sets. The impact of batteries was nearly impossible to discern as recently as 2023, but data from May and June of 2025 shows batteries pulling in lots of power at mid-day, and using it in the early evening to completely offset what would otherwise be an enormous surge in the use of natural gas.

Not every state has the sorts of solar resources available to California. But the economics of solar power suggest that other states are likely to experience this sort of growth in the coming years. And, while the Trump administration has been openly hostile to solar power from the moment it took office, so far there is no sign of that hostility at the grid level.

John is Ars Technica’s science editor. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Biochemistry from Columbia University, and a Ph.D. in Molecular and Cell Biology from the University of California, Berkeley. When physically separated from his keyboard, he tends to seek out a bicycle, or a scenic location for communing with his hiking boots.