Sometimes, new data raises more questions than it answers.

Today, the North Pacific right whale is severely endangered, meaning that it’s at risk of suffering the same fate as the mammoth. Credit: Credit: Brenda K. Rone via NOAA

In a recent study, University of Alaska Fairbanks paleontologist Matthew Wooller and his colleagues radiocarbon-dated what they thought were pieces of two mammoth vertebrae, only to get a whale of a surprise and a whole new mystery.

At first glance, it looked like Wooller and his colleagues might have found evidence that mammoths lived in central Alaska just 2,000 years ago. But ancient DNA revealed that two “mammoth” bones actually belonged to a North Pacific right whale and a minke whale—which raised a whole new set of questions. The team’s hunt for Alaska’s last mammoth had turned into an epic case of mistaken identity, starring two whale species and a mid-century fossil hunter.

“The first signs that something was amiss”

The aptly named Wooller and his team have radiocarbon-dated more than 300 mammoth fossils over the last four years, looking for the last survivors of the wave of extinctions that wiped out woolly mammoths and other Pleistocene megafauna at the end of the last Ice Age. Two specimens stood out immediately. Based on the radiocarbon dates, two mammoths had lived near Fairbanks as recently as 2,800 and 1,900 years ago. Wooller and his colleagues had been looking for the youngest woolly mammoth specimen in Alaska but were completely mystified.

“The radiocarbon data and their associated stable isotope data were the first signs that something was amiss,” wrote Wooller and his colleagues in their recent paper. At first, though, they had no idea quite how amiss things were.

Those unlikely radiocarbon dates came from a pair of vertebral growth plates (structures at the top and bottom of the vertebra where new bone forms during growth). The University of Alaska Museum of the North’s inventory listed them as mammoth bones from a site called Dome Creek, near Fairbanks, Alaska. DNA testing and some sleuthing by Wooller and his colleagues revealed that the specimens weren’t mammoth bones, and they were probably never even at Dome Creek.

Hunting mammoths in Alaska

Setting these two samples aside, the fossil record of mammoths in Alaska ends around 11,000 years ago. But hundreds of mammoth fossils in museum collections haven’t been directly dated, so it’s hard to say for sure that this is when the species died out. Ancient DNA frozen in permafrost, however, has offered some tantalizing hints that at least a few mammoths may have been stomping around mainland Alaska, northwestern Canada, and parts of Russia as recently as 5,700 years ago. If so, that could be a key piece of evidence in the Ice Age cold case about what killed off the Pleistocene megafauna: human hunters or the changing world.

Wooller and his colleagues have been searching since 2022 through a crowdfunding project called Adopt-a-Mammoth; de-extinction company Colossal Biosciences is also involved. Adopting a specimen costs $380 and comes with a photo, a copy of the test results, and the option to name your mammoth. (Tusky McTuskface, anyone?)

“Radiocarbon dates are expensive,” wrote the researchers in their recent paper. “However, dating specimens usually needs to occur before time and resources are devoted to additional analyses of specimens, such as DNA.” The Adopt-a-Mammoth project has dated around 300 mammoth fossils so far, hoping to find the youngest mammoth in the Alaskan fossil record. But the two vertebral growth disks from Dome Creek were way off the charts.

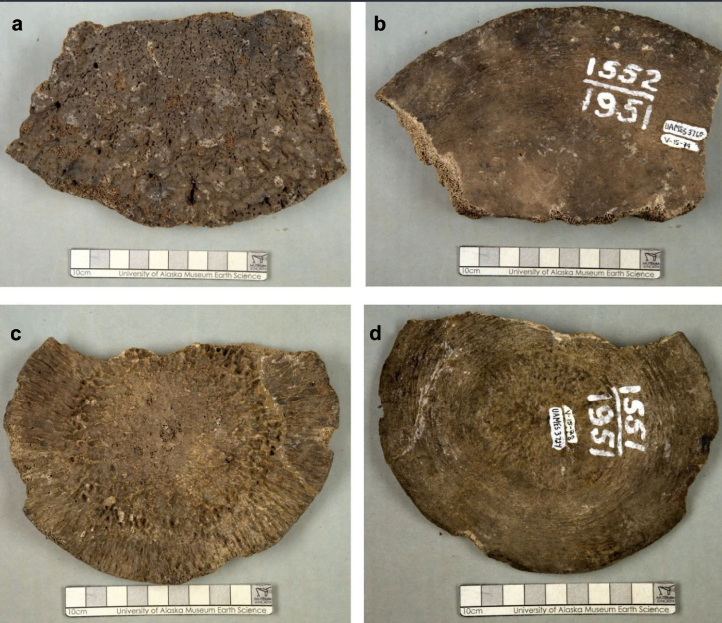

These are the two vertebral growth disks in question, so it’s not hard to see why a visual identification went wrong.

Credit: Wooller et al. 2026

These are the two vertebral growth disks in question, so it’s not hard to see why a visual identification went wrong. Credit: Wooller et al. 2026

“The ancient DNA came to our rescue”

Ratios of nitrogen and carbon stable isotopes in the bones also didn’t add up. These elements can offer clues about ancient diets (at a molecular level, you really are what you eat), but they suggest that two mammoths from what is now Fairbanks ate a diet heavy in protein from marine sources. In fact, their diets looked more like those of modern whales. That’s extremely weird for mammoths that lived 400 kilometers from the nearest beach. You could even say it looked fishy.

At this point, Wooller and his colleagues were starting to suspect that they weren’t looking at mammoth bones at all.

Vertebral growth disks aren’t one of the most species-diagnostic bones in the body, especially after spending a millennium or two underground. The researchers called in a handful of mammoth and whale experts for backup; each of them pretty much shrugged and said that they couldn’t tell what sort of animal the bones had come from just by looking. Seventy-five years ago, early 1950s fossil collector Otto Geist had identified the bones as mammoth based on their shape, but he may have been a little overconfident.

“The ancient DNA came to our rescue to secure the specimens’ true identity,” wrote Wooller and his colleagues. It also opened up a whole new mystery: The two bone disks belonged to a North Pacific right whale and a minke whale, neither of which has ever lived in the middle of mainland Alaska.

The mystery of the lost whales

So much for impossibly young mammoths! Wooller and his colleagues were left to explain how the same part from two different whales, of two different species, traveled 400 kilometers inland to Dome Creek. They saw three possible explanations: Either carnivores brought the bones to the site, humans brought the bones to the site, or the whales swam themselves to the site. And none of those explanations quite fit.

“Wayward cetaceans have been documented in inland waterways across the world, including Alaskan rivers such as the Yukon and Tanana,” wrote Wooller and his colleagues. And minke whales in particular have shown up as far as 1,000 kilometers inland. Dome Creek is miles from the nearest large river, the Tanana, but even so, if it had just been the minke whale bone, Wooller and his colleagues might have convinced themselves that they had stumbled across one very intrepid—or very lost—whale.

“That two individual whales of different species have made this improbable journey, died naturally, and left behind the very same skeletal element is not reasonable in our estimate,” wrote Wooller and his colleagues.

That left carnivores or people. No species of carnivore, past or present, was likely to have dragged bones hundreds of kilometers. People, on the other hand, transport all sorts of things over vast distances. And vertebral growth plates are surprisingly useful as plates, trays, or cutting boards. The only problem is that archaeologists haven’t found whale bones at any other sites in inland Alaska, meaning that they apparently weren’t a very common trading item. File that under “possible but not likely.”

Somehow, the best explanation is that the whale bones weren’t even from Dome Creek in the first place.

Lost and found at the museum

Paleontologist Otto Geist gathered a truly staggering number of Pleistocene bones from sites all over Alaska, and 1951 was an especially busy year for him. In addition to the 181 specimens from Dome Creek, Geist also returned to the museum with bones he had unearthed at several sites along the western coast of Alaska. It turned out that on the very same day the museum received the Dome Creek specimens, they also accepted a collection of bones from a site called Dexter Point, on the coast of Norton Bay.

“It is possible that the two whale bones examined in the current study derived from this Norton Bay locale and were inadvertently included with the Dome Creek assemblage,” wrote Wooller and his colleagues, although they acknowledge, “Ultimately, this may never be completely resolved.”

Meanwhile, the Adopt-a-Mammoth project continues, having provided an object lesson in the importance of “fully investigating anomalous radiocarbon results,” as the researchers put it. In other words, if your data looks fishy, it might actually be a whale.

Journal of Quaternary Science, 2026 DOI: 10.1002/jqs.70040