Avellone recaps his journey from learning on a TRS-80 to today.

Chris Avellone, storied game designer. Credit: Chris Avellone

Chris Avellone wants you to have a good time.

People often ask creatives—especially those in careers some dream of entering—”how did you get started?” Video game designers are no exception, and Avellone says that one of the most important keys to his success was one he learned early in his origin story.

“Players are selfish,” Avellone said, reflecting on his time designing the seminal computer roleplaying game Planescape: Torment. “The more you can make the experience all about them, the better. So Torment became that. Almost every single thing in the game is about you, the player.”

The true mark of a successful game is when players really enjoy themselves, and serving that essential egotism is one of the fundamental laws of game design.

It’s a lesson he learned long before he became an internationally renowned game designer, before Fallout 2 and Planescape: Torment were twinkles in the eyes of Avellone and his co-workers at Interplay. Avellone’s first introduction to building fictional worlds came not from the digital realm but from the analog world of pen and paper roleplaying games.

Table-top takeaways

Avellone discovered Dungeons and Dragons at the tender young age of nine, and it was a formative influence on his creative life and imagination.

“Getting exposed to the idea of Dungeons and Dragons early was a wake-up call,” he told me. “‘Oh wow, it’s like make believe with rules!’—like putting challenges on your imagination where not everything was guaranteed to succeed, and that made it more fun. However, what I noticed is that I wasn’t usually altering the systems drastically, it was more using them as a foundation for the content.”

As is so often the case with RPG developer origin stories, it began with Dungeons & Dragons. Credit: Scott Swigart (CC BY 2.0)

At first, Avellone wasn’t interested in engineering the games and stories himself. He wanted a more passive role, but life had different ideas.

“I never started out with a desire to be the game master,” Avellone remembered. “I wanted to be one of the players, but once it became clear that nobody else in my friend circle really wanted to be a game master—to be fair, it was a lot of work—I bit the bullet and tried my hand at it. Over time, I discovered I really enjoyed helping tell an interactive story with the players.”

That revelation, that he preferred being the one crafting the world and guiding the experience, led to some early experiments away from the table as well.

“I never pursued programming for a career, which is probably to the benefit of the world and engineering everywhere,” he joked. But he did start tinkering very young, inspired by the fantasy text adventure games he played as a kid. “I wanted to construct adventure games in the vein of the Scott Adams games… so I attempted to learn basic coding on the TRS-80 in order to do so. The results were a steaming, buggy mess, but [the experience] did give insights into how games operate under the hood.”

It was a different era, however, bereft of many of the resources that aspiring young game developers have at their fingertips today.

“It being the early ’80s, there wasn’t much access to Internet forums and online training courses like today,” Avellone said. “It was mostly book learning from various programming manuals available on order or from the library. These programming attempts were always solo endeavors at fantasy-style sword and sorcery adventures, and I definitely would have benefited from a community or at least one other person of skill who I could ask questions.”

Despite all of his remarkable success in the space, Avellone didn’t originally dream of creating video games.

“Designing computer games was something I sort of fell into,” he told me. “The idea of a game designer was an almost unheard of career at the time and wasn’t even on my radar. I wanted to write pen and paper modules, adventure and character books, and comic books. As it turned out, though, that can be a miserable way to try and make a living, so when an opportunity came to work in the computer game industry, I took it with the expectation that I’d still use my off time to pursue comics, [pen and paper] writing, etc. But like with game mastering, I found computer game design and narrative design to be fun in itself, and it ended up being the bulk of my career. I did get the opportunity to write modules and comic books later on, but writing for games became my focus, as it was akin to being a virtual game master.”

Like many of the engineers and developers of that era, toiling in their garages and quietly building the future of computing, young Chris Avellone used other creator’s work as a foundation.

“One technique I tried was dissecting existing game engines,” he recalls, “more like an adventure game framework, and then finding ways to alter the content layer to create the game. But the attempts rarely compiled without a stream of errors.”

The shine moment

Every failure was an opportunity to learn, however, and like his experiences telling collaborative stories with his friends in Dungeons and Dragons, they taught him a number of lessons that would serve him later in his career. In our interview, he returned again and again to the player-first mentality that drives his design ethos.

First and foremost, a designer needs to “understand your players and understand why they are there,” Avellone said. “What is their power fantasy?”

Beyond that, every player, whether in a video game or a tabletop roleplaying adventure, should have an opportunity to stand in the spotlight.

“That shine moment is important because it gives everyone the chance to be a hero and to make a difference,” he explained. “The best adventures are the ones where you can point to how each player was instrumental in its success because of how they designed or role-played their character.”

And players should be able to get to that moment in the way they want, not the one most convenient to you, the game master or designer.

“Not everyone plays the way you do,” Avellone said, “and your job as game master is not to dictate how they choose to play or force them into a certain game mode. If a player is a min-maxer who doesn’t care much for the story, that shouldn’t be a problem. If the player is a heavy role-player, they should have some meat for their interactions. This applies strongly to digital game design. If players want to skip dialogue and story points, that’s how they choose to play the game, and they shouldn’t be crushingly penalized for their play style. It’s not your story, it should be a shared experience between the developer and player.”

A core part of his design philosophy, this was a takeaway from pen-and-paper games that Avellone has deployed throughout his career in video games.

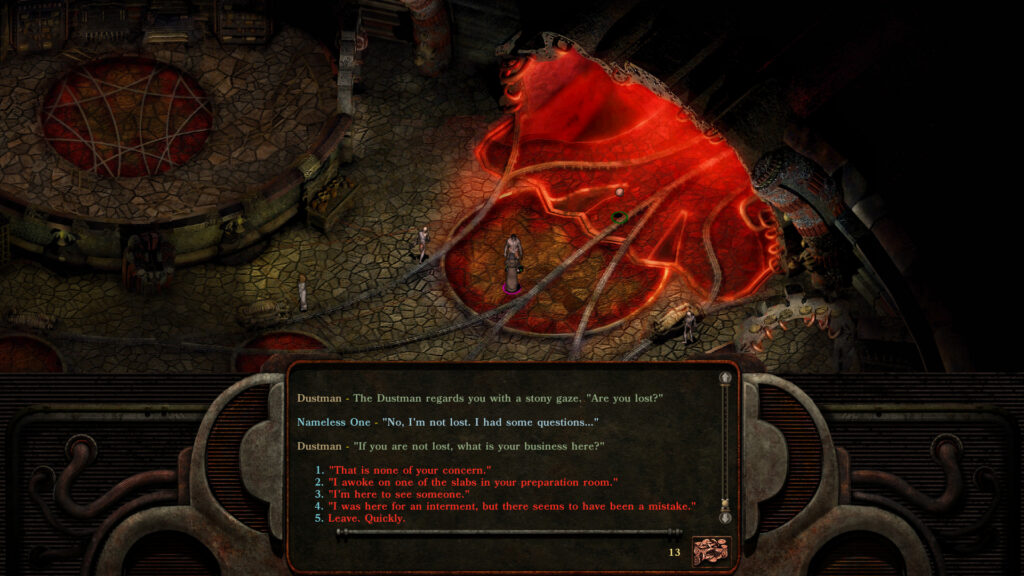

“The first application was Planescape: Torment,” Avellone remembered.

Working on Planescape: Torment

It was 1995. Interplay had recently acquired the Planescape license from Wizards of the Coast, formerly TSR, the company behind Dungeons and Dragons. Interplay was looking for ideas for a video game adaptation and brought in Avellone for an interview. At the time, he was writing for Hero Games, a tabletop RPG publisher. Avellone was hired onto the project as a junior director after he sold the idea of a game where death was only the beginning.

That idea—the springboard that launched a successful, decades-spanning career—originated in Avellone’s frustration with save scumming, the process of repeatedly reloading save games to achieve the best result.

“Save scumming in RPGs up to that point felt like a waste of everyone’s time,” Avellone said. “If you died, you either reloaded or you quit. If they quit, you might lose them permanently. So I felt if you removed the middle man and just automatically respawned the character in interesting places and ways, that could keep the experience seamless and keep the flow of the adventure going. This didn’t quite work, because players were so used to save scumming and would still feel they had failed in some way. I was fighting typical gaming conventions and gaming habits at that point.”

That idea of death being just another narrative element rather than a fail state is emblematic of another pillar of Avellone’s design philosophy, also drawn from pen-and-paper games: Regardless of what happens, the story must go on.

“Let the dice fall where they may,” Avellone explained. “It will result in more interesting gaming stories. This was a hard one for me initially, because I would get so locked into a certain character, NPC, or letting a PC survive, that I would fight random chance to keep my story or their arc intact. This was a mistake and a huge missed opportunity. If the players have no fear of death or annoying adversaries who never seem to die because you are fudging the dice rolls to prevent them from being killed, then it undermines much of the drama, and it undermines their eventual success.”

Avellone is known for many classics, but among hardcore RPG fans, Planescape Torment stands particularly tall. Credit: Beamdog

After Planescape: Torment, which received nearly universal critical acclaim, Avellone continued to evolve best practices for giving players what they wanted. He eventually landed on the idea that player input could be useful even before development begins.

“I would often do pre-game interviews with different players,” he recounted, “to get a sense of where they hoped their character arc would go, how they wanted to play.”

Lessons from Fallout Van Buren

Avellone expanded that process dramatically for Fallout Van Buren, Interplay’s vision for Fallout 3. He and the team built a Fallout tabletop role playing game to playtest some of the systems that would be implemented in the (ultimately cancelled) video game.

“For the Fallout pen-and-paper we were doing for Fallout Van Buren, for example, doing those examinations proved helpful because there were so many different character builds—including ghouls and super mutants, as well as new archetypes like Science Boy—that you wanted to make sure you were creating an experience where everyone had the chance to shine.”

Though Van Buren never saw the light of day, Avellone has said that some of the elements from that design found their way into the wildly popular Fallout: New Vegas, a project for which Avellone served as senior designer (as well as project director for much of the DLC).

Another lesson he learned at the table is that you should never honor a player’s accomplishment with a reward if you plan to immediately snatch it away.

“Don’t give, then take away,” Avellone warns. “One of the worst mistakes I made was after an excruciatingly long treasure hunt for one of the biggest hordes in the world, I took away all the unique items the characters had struggled to win at the start of the very next adventure. While I knew they would get the items back, the players didn’t, and that almost caused a mutiny.”

A screenshot from Fallout Van Buren. Credit: No Mutants Allowed

I asked Avellone if his earliest experience playing with other people’s code or sitting around rolling dice with his friends had a throughline to his work today. It was clear in his answer, and throughout our interview, that the little boy who fell in love with architecting worlds of fantasy and adventure in his imagination is still very much alive in the seasoned developer building digital worlds for players today. The core idea persists: It’s all about the players, about their connection to your story and your world.

“It still has a strong impact on my game design today,” he told me. “It’s still important to me to see the range of archetypes and builds a player can make. How to make that feel important in a unique way, and how to structure plots and interactions so you try and keep the character goals so they cater to the player’s selfishness. Instead of some outward, forced goal you place on the player… find a way to make the internal player motivation match the goals in-game, and that makes for a stronger experience.”

Avellone carries that philosophy forward into his current project. He recently signed on to help develop the inaugural project at Republic Games, the studio founded by video game writer Adam Williams, formerly of Quantic Dream. The studio is developing a dystopian fantasy game that revolves around a scrappy rebellion fighting to overthrow brutal, tyrannical oppression.

“Some discussions at Republic Games have fallen back on old RPG designs in the past,” he teased, “As some older designs seemed relevant examples for how to solve a potential arc and direction in the game… but I’ll share that story after the game comes out.”