If they improve further, AI weather models may very well become the gold standard.

A satellite image of Erin shortly after becoming a Category 5 hurricane on Saturday. Credit: NOAA

In early June, shortly after the beginning of the Atlantic hurricane season, Google unveiled a new model designed specifically to forecast the tracks and intensity of tropical cyclones.

Part of the Google DeepMind suite of AI-based weather research models, the “Weather Lab” model for cyclones was a bit of an unknown for meteorologists at its launch. In a blog post at the time, Google said its new model, trained on a vast dataset that reconstructed past weather and a specialized database containing key information about hurricanes tracks, intensity, and size, had performed well during pre-launch testing.

“Internal testing shows that our model’s predictions for cyclone track and intensity are as accurate as, and often more accurate than, current physics-based methods,” the company said.

Google said it would partner with the National Hurricane Center, an arm of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Service that has provided credible forecasts for decades, to assess the performance of its Weather Lab model in the Atlantic and East Pacific basins.

All eyes on Erin

It had been a relatively quiet Atlantic hurricane season until a few weeks ago, with overall activity running below normal levels. So there were no high-profile tests of the new model. But about 10 days ago, Hurricane Erin rapidly intensified in the open Atlantic Ocean, becoming a Category 5 hurricane as it tracked westward.

From a forecast standpoint, it was pretty clear that Erin was not going to directly strike the United States, but meteorologists sweat the details. And because Erin was such a large storm, we had concerns about how close Erin would get to the East Coast of the United States (close enough, it turns out, to cause some serious beach erosion) and its impacts on the small island of Bermuda in the Atlantic.

When a storm is active, it can be difficult to discern which of the many different models provides the best forecast for a tropical cyclone. We can look at their performance with the storm to date, but even then, there are uncertainties. Only after the fact can we run the numbers and see which models did the best in predicting where a tropical system would go and how strong it got.

Now that Erin has dissipated, we can make such a determination, and in the biggest test of the Atlantic season to date, Google’s Weather Lab performed the best at periods of 72 hours or less. (This is a three-day forecast for the storm).

How did DeepMind do?

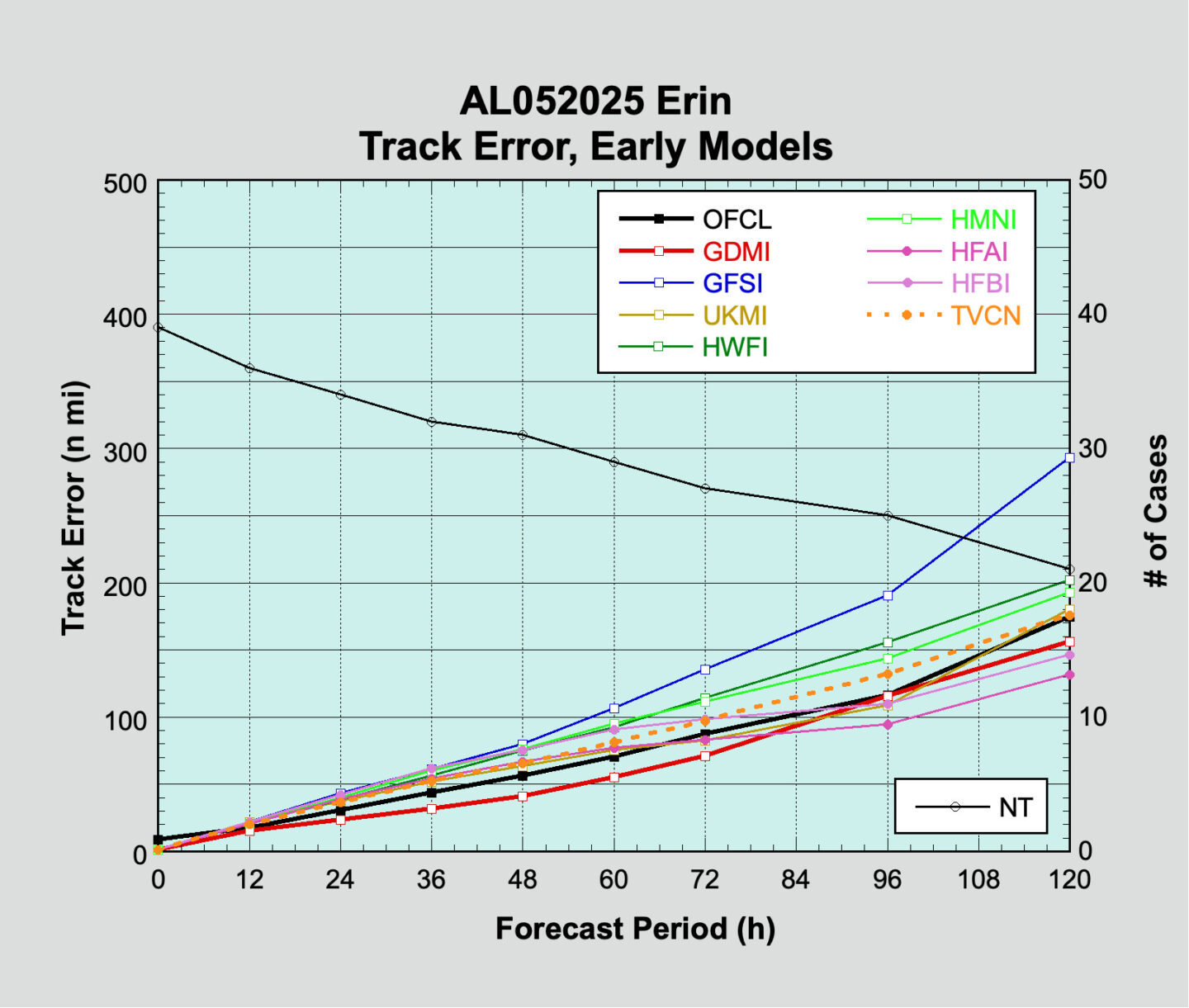

You can see the data for yourself in the charts below, compiled by James Franklin, former chief of the hurricane specialist unit at the National Hurricane Center. Google’s model is shown as GDMI on these graphs.

Track error performance for Hurricane Erin. Credit: James Franklin/Blue Sky

In terms of track, Google’s model not only beat the “official” track forecast from the National Hurricane Center but also bested a number of physics-based models that make global forecasts as well as hurricane-specific models.

A physics-based model is a traditional forecast model based on complex equations. Also called numerical weather prediction, such models take initial atmospheric conditions and then crunch through calculations to determine how the atmosphere will change over time.

This process requires intensive computational power but has historically served meteorology well. Error trends in hurricane track forecasts have dropped significantly over the last quarter of a century as computer hardware has improved and our ability to gather and input real-time atmospheric conditions has strengthened.

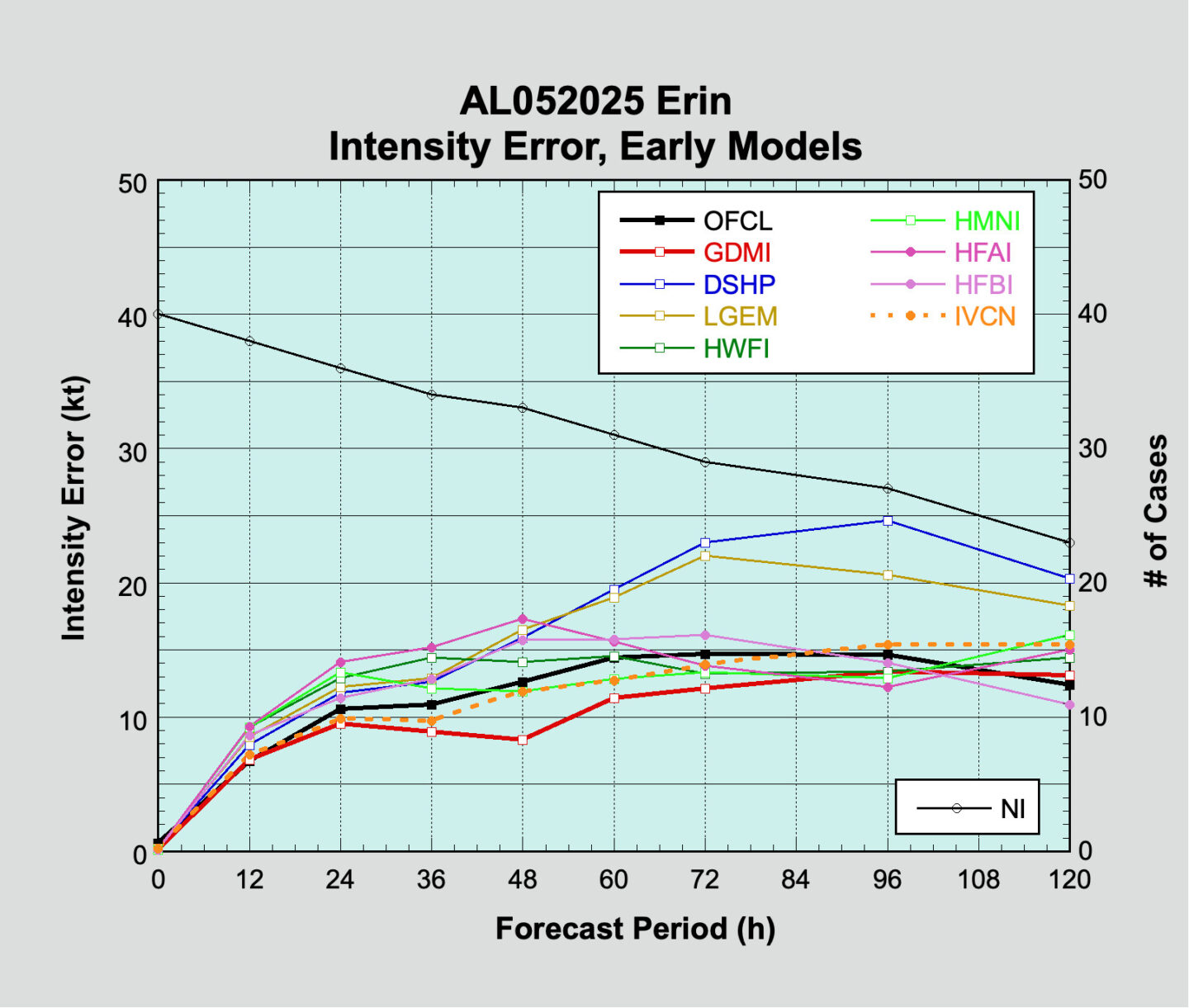

Intensity error for Hurricane Erin. Credit: James Franklin/Blue Sky

Similarly to track forecasts, Google’s model also outperformed other models for the first 72 hours when it came to intensity forecasts. Its performance at two days is particularly striking.

Time to take AI weather modeling seriously

There are a couple of additional notes to add here. The TVCN and IVCN models shown on the graphs represent “consensus” models for track and intensity that are closely watched by forecasters at the hurricane center. Their output is not generally made public, but the models essentially provide a bias-corrected average of some of the best models. In this context, bias-corrected means that the software corrects for known forecast biases in various models. So the fact that Google’s model beat the consensus models is significant.

From a forecast standpoint, the period of three to five days out is the most important. This is when important decisions about evacuations and other hurricane preparations need to be made to leave time for them to be put into action. Accordingly, we would like to see AI models perform better in this forecast range.

Nevertheless, the key takeaway here is that AI weather modeling is continuing to make important strides. As forecasters look to make predictions about high-impact events like hurricanes, AI weather models are quickly becoming a very important tool in our arsenal.

This doesn’t mean Google’s model will be the best for every storm. In fact, that is very unlikely. But we certainly will be giving it more weight in the future.

Moreover, these are very new tools. Google’s Weather Lab, along with a handful of other AI weather models, has already shown equivalent skill to the best physics-based models in a short time. If these models improve further, they may very well become the gold standard for certain types of weather prediction.

Eric Berger is the senior space editor at Ars Technica, covering everything from astronomy to private space to NASA policy, and author of two books: Liftoff, about the rise of SpaceX; and Reentry, on the development of the Falcon 9 rocket and Dragon. A certified meteorologist, Eric lives in Houston.