flukes, flops, and failures

Ars chats with co-authors Lindsey Fitzharris and Adrian Teal about their delightful new children’s book.

In 1890, a German scientist named Robert Koch thought he’d invented a cure for tuberculosis, a substance derived from the infecting bacterium itself that he dubbed Tuberculin. His substance didn’t actually cure anyone, but it was eventually widely used as a diagnostic skin test. Koch’s successful failure is just one of the many colorful cases featured in Dead Ends! Flukes, Flops, and Failures that Sparked Medical Marvels, a new nonfiction illustrated children’s book by science historian Lindsey Fitzharris and her husband, cartoonist Adrian Teal.

A noted science communicator with a fondness for the medically macabre, Fitzharris published a biography of surgical pioneer Joseph Lister, The Butchering Art, in 2017—a great, if occasionally grisly, read. She followed up with 2022’s The Facemaker: A Visionary Surgeon’s Battle to Mend the Disfigured Soldiers of World War I, about a WWI surgeon named Harold Gillies who rebuilt the faces of injured soldiers.

And in 2020, she hosted a documentary for the Smithsonian Channel, The Curious Life and Death Of…, exploring famous deaths, ranging from drug lord Pablo Escobar to magician Harry Houdini. Fitzharris performed virtual autopsies, experimented with blood samples, interviewed witnesses, and conducted real-time demonstrations in hopes of gleaning fresh insights. For his part, Teal is a well-known caricaturist and illustrator, best known for his work on the British TV series Spitting Image. His work has also appeared in The Guardian and the Sunday Telegraph, among other outlets.

The couple decided to collaborate on children’s books as a way to combine their respective skills. Granted, “[The market for] children’s nonfiction is very difficult,” Fitzharris told Ars. “It doesn’t sell that well in general. It’s very difficult to get publishers on board with it. It’s such a shame because I really feel that there’s a hunger for it, especially when I see the kids picking up these books and loving it. There’s also just a need for it with the decline in literacy rates. We need to get people more engaged with these topics in ways that go beyond a 30-second clip on TikTok.”

Their first foray into the market was 2023’s Plague-Busters! Medicine’s Battles with History’s Deadliest Diseases, exploring “the ickiest illnesses that have infected humans and affected civilizations through the ages”—as well as the medical breakthroughs that came about to combat those diseases. Dead Ends is something of a sequel, focusing this time on historical diagnoses, experiments, and treatments that were useless at best, frequently harmful, yet eventually led to unexpected medical breakthroughs.

Failure is an option

The book opens with the story of Robert Liston, a 19th-century Scottish surgeon known as “the fastest knife in the West End,” because he could amputate a leg in less than three minutes. That kind of speed was desirable in a period before the discovery of anesthetic, but sometimes Liston’s rapid-fire approach to surgery backfired. One story (possibly apocryphal) holds that Liston accidentally cut off the finger of his assistant in the operating theater as he was switching blades, then accidentally cut the coat of a spectator, who died of fright. The patient and assistant also died, so that operation is now often jokingly described as the only one with a 300 percent mortality rate, per Fitzharris.

Liston is the ideal poster child for the book’s theme of celebrating the role of failure in scientific progress. “I’ve always felt that failure is something we don’t talk about enough in the history of science and medicine,” said Fitzharris. “For everything that’s succeeded there’s hundreds, if not thousands, of things that’s failed. I think it’s a great concept for children. If you think that you’ve made mistakes, look at these great minds from the past. They’ve made some real whoppers. You are in good company. And failure is essential to succeeding, especially in science and medicine.”

“During the COVID pandemic, a lot of people were uncomfortable with the fact that some of the advice would change, but to me that was a comfort because that’s what you want to see scientists and doctors doing,” she continued. “They’re learning more about the virus, they’re changing their advice. They’re adapting. I think that this book is a good reminder of what the scientific process involves.”

The details of Liston’s most infamous case might be horrifying, but as Teal observes, “Comedy equals tragedy plus time.” One of the reasons so many of his patients died was because this was before the broad acceptance of germ theory and Joseph Lister’s pioneering work on antiseptic surgery. Swashbuckling surgeons like Liston prided themselves on operating in coats stiffened with blood—the sign of a busy and hence successful surgeon. Frederick Treves once observed that in the operating room, “cleanliness was out of place. It was considered to be finicking and affected. An executioner might as well manicure his nails before chopping off a head.”

“There’s always a lot of initial resistance to new ideas, even in science and medicine,” said Teal. “A lot of what we talk about is paradigm shifts and the difficulty of achieving [such a shift] when people are entrenched in their thinking. Galen was a hugely influential Roman doctor and got a lot of stuff right, but also got a lot of stuff wrong. People were clinging onto that stuff for centuries. You have misunderstanding compounded by misunderstanding, century after century, until somebody finally comes along and says, ‘Hang on a minute, this is all wrong.’”

You know… for kids

Writing for children proved to be a very different experience for Fitzharris after two adult-skewed science history books. “I initially thought children’s writing would be easy,” she confessed. “But it’s challenging to take these high-level concepts and complex stories about past medical movements and distill them for children in an entertaining and fun way.” She credits Teal—a self-described “man-child”—for taking her drafts and making them more child-friendly.

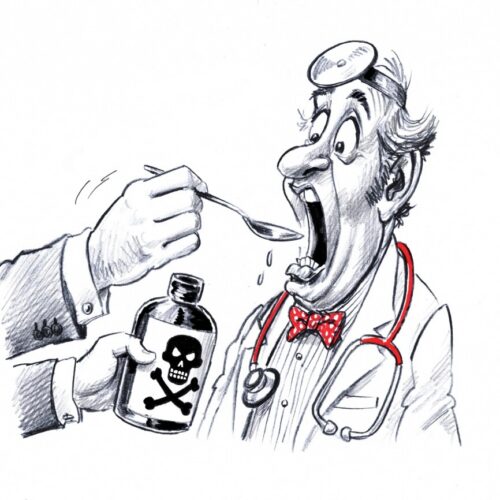

Teal’s clever, slightly macabre illustrations also helped keep the book accessible to its target audience, appealing to children’s more ghoulish side. “There’s a lot of gruesome stuff in this book,” Teal said. “Obviously it’s for kids, so you don’t want to go over the top, but equally, you don’t want to shy away from those details. I always say kids love it because kids are horrible, in the best possible way. I think adults sometimes worry too much about kids’ sensibilities. You can be a lot more gruesome than you think you can.”

The pair did omit some darker subject matter, such as the history of frontal lobotomies, notably the work of a neuroscientist named Walter Freeman, who operated an actual “lobotomobile.” For the authors, it was all about striking the right balance. “How much do you give to the kids to keep them engaged and interested, but not for it to be scary?” said Fitzharris. “We don’t want to turn people off from science and medicine. We want to celebrate the greatness of what we’ve achieved scientifically and medically. But we also don’t want to cover up the bad bits because that is part of the process, and it needs to be acknowledged.”

Sometimes Teal felt it just wasn’t necessary to illustrate certain gruesome details in the text—such as their discussion of the infamous case of Phineas Gage. Gage was a railroad construction foreman. In 1848, he was overseeing a rock blasting team when an explosion drove a three-foot tamping iron through his skull. “There’s a horrible moment when [Gage] leans forward and part of his brain drops out,” said Teal. “I’m not going to draw that, and I don’t need to, because it’s explicit in the text. If we’ve done a good enough job of writing something, that will put a mental picture in someone’s head.”

Miraculously, Gage survived, although there were extreme changes in his behavior and personality, and his injuries eventually caused epileptic seizures, one of which killed Gage in 1860. Gage became the index case for personality changes due to frontal lobe damage, and 50 years after his death, the case inspired neurologist David Ferrier to create brain maps based on his research into whether certain areas of the brain controlled specific cognitive functions.

“Sometimes it takes a beat before we get there,” said Fitzharris. “Science builds upon ideas, and it can take time. In the age of looking for instantaneous solutions, I think it’s important to remember that research needs to allow itself to do what it needs to do. It shouldn’t just be guided by an end goal. Some of the best discoveries that were made had no end goal in mind. And if you read Dead Ends, you’re going to be very happy that you live in 2025. Medically speaking, this is the best time. That’s really what Dead Ends is about. It’s a celebration of how far we’ve come.”

Jennifer is a senior writer at Ars Technica with a particular focus on where science meets culture, covering everything from physics and related interdisciplinary topics to her favorite films and TV series. Jennifer lives in Baltimore with her spouse, physicist Sean M. Carroll, and their two cats, Ariel and Caliban.