A 5,500-year-old fossil from Colombia has scientists rethinking syphilis origins.

When King Charles VIII of France occupied Naples in 1495, his army of nearly 20,000 mercenaries became the ground zero of the “Great Pox,” the first massive venereal syphilis pandemic in Europe, which went on to cause up to 5 million deaths. For a long time, the siege of Naples was considered the first time syphilis entered European accounts and culture. “But the evolutionary history of Treponema pallidum, the lineage of bacteria including the one that causes syphilis, goes way deeper in time,” says Elizabeth Nelson, an anthropologist at Southern Methodist University.

Nelson and her colleagues found a 5,500-year-old Treponema pallidum genome in an individual excavated from a rock shelter in Colombia—a discovery that shows pathogens causing treponemal diseases like syphilis, bejel, or yaws are several millennia older than we thought. And this means we might have been thinking about the origins of syphilis in an entirely wrong way.

The blame game

While the French occupation of Naples did not introduce syphilis to the world, it created the perfect storm that shaped the perception of this disease and its origins for centuries to come. The first ingredient of this storm was the French army and its leader. Charles VIII invaded Naples with a vast melting pot of brigands and mercenaries from all over Europe, including the French, Swiss, Poles, and Spaniards. The king himself wasn’t exactly the epitome of morality. Chroniclers like Johannes Burckard noted his “fondness of copulation” and reported that, once he’d been with a woman, he “cared no more about her” and immediately sought another partner—a behavior eagerly mirrored by his soldiers.

The second ingredient was the city of Naples, which, in the 15th century, was famous as the center of luxury and sex. When the city surrendered and opened its gates, the invading army spent months on what Joseph Grünpeck, a secretary to the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I, described as “gluttony, debauchery, and consorting with prostitutes.” This created the ideal set of conditions for syphilis, a sexually transmitted disease, to spread massively among the armies. When the mercenaries, incapable of fighting anymore, deserted the infected army and fled to their home countries, the disease rapidly spread across Europe. These conditions also immediately defined the narrative about syphilis in terms of cultural and national blame games.

The Neapolitans called syphilis Morbus Gallicus, which means the French disease. The French returned the favor and called it the Neapolitan disease. The English naturally called it the French Pox, and so on. Ultimately, fingers ended up pointing at a few Spaniards from Charles VIII’s army. They allegedly served as crew members on Columbus’ ships that returned from the New World in 1493, just one year before the siege of Naples started. Syphilis was declared a “gift” Columbus brought to Europe from the Americas, a curse the New World cast upon the old one.

The blame game naturally assumed syphilis must have had a single place of origin, be it Naples, France, Europe, or the Americas. The 5,500-year-old Treponema pallidum genome discovered by Nelson and her colleagues suggests it might not have been the case at all. “I would not say our work makes popular syphilis origin stories irrelevant, but it shows there’s more ecological and evolutionary depth here,” Nelson says.

The accidental pathogen

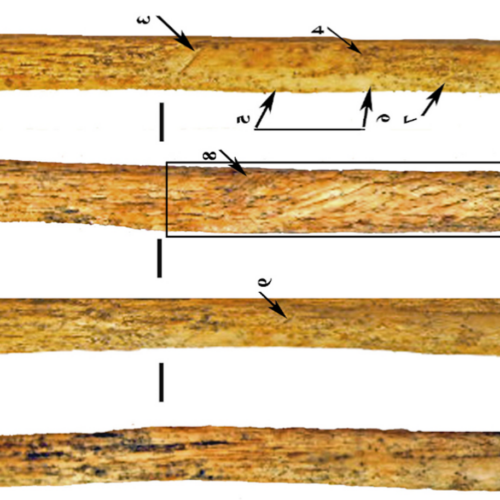

The discovery was, in a way, a lucky break. The team was sequencing the DNA of an individual excavated from the Tequendama I rock shelter, located in the Sabana de Bogotá, Colombia, as part of a broader research project on the population history of the Americas. The individual in question, labeled TE1-3, was an adult male hunter-gatherer who lived in the Middle Holocene, roughly 5,500 years ago. “We weren’t looking for the origins of syphilis, this wasn’t the main focus of our research,” says Nasreen Broomandkhoshbacht, a geneticist at the University of Vermont and co-author of the study.

Typically, scientists hunting for ancient Treponema genomes look for bones with telltale signs of treponematosis like altered shins or pitted skull lesions. But the skeleton of TE1-3 showed no macroscopic signs of infection. Usually, this would make it a poor candidate for pathogen recovery. However, thanks to the sheer volume of data generated—1.5 billion fragments of genetic material—scientists could detect traces of Treponema pallidum.

Despite the bacterial DNA making up a minuscule portion of the total sequencing data, the team succeeded in reconstructing the ancient pathogen’s genome, and right from the start, it appeared a little bit special. The treponema pallidum lineage today comprises three subspecies responsible for syphilis, bejel, and yaws. “We noticed that the genome we recovered differed from those three much more than they differ from each other,” Broomandkhoshbacht says. That indicates the newly discovered bacterium wasn’t a direct ancestor of modern syphilis, yaws, or bejel. “It was a sister lineage that diverged from all known modern subspecies approximately 13,700 years ago in Late Pleistocene,” says Davide Bozzi, a computational biologist at the University of Lausanne and lead author of the study.

About 13,700 years ago was roughly when humans first started populating South America and rapidly spread around the continent. And, based on this discovery, the bacteria of the Treponema pallidum lineage were already diverse and capable of infecting people by then. This Late Pleistocene divergence, the authors note in their study, hints at the ancient pan-human distribution. Various Treponema pallidum subspecies were probably our fellow travelers spreading globally with the first humans that migrated out of Africa.

But there’s much more we need to learn before the “Columbian” syphilis origin debate is settled.

Beyond the Columbian story

While the 1495 siege of Naples remains the moment syphilis etched itself into the European psyche as a new and terrifying plague, it was likely just one violent flare-up in a relationship between humans and Treponema pathogens that spans continents and millennia. What we don’t know is when and where the important turning points in this relationship took place.

It’s unclear when and why Treponema pallidum evolved its sexual transmission, so evidently present in the subspecies that caused the outbreak in Naples. It’s also unclear whether the 1495 pandemic was triggered by a newly imported strain or a mutation of a lineage already present in Europe. The team hopes analyzing other ancient pathogen genomes hosted by people from different places on the globe and different social contexts—hunter-gatherers, farmers, city dwellers—will answer at least some of these questions.

The problem is, it’s hard to infer a specific pathogen’s features from ancient genomes. “With the data we have today, we can’t say anything about the virulence of this ancient Treponema pallidum subspecies, about how the symptoms of the disease it caused looked like, or about its mode of transmission,” Bozzi says.

What we do know, however, is that thousands of years ago, the Treponema pallidum lineage was likely way more diverse than it is today. “In the future we’d love to look at broader ecological interactions between humans, animals, the environment, and the pathogens,” says Nelson. “We’d love to explore this diversity further.”

Science, 2026. DOI: 10.1126/science.adw3020

Jacek Krywko is a freelance science and technology writer who covers space exploration, artificial intelligence research, computer science, and all sorts of engineering wizardry.