Riding high in IMSA but pulling out of WEC paints a complicated picture for the factory team.

Porsche didn’t win this year’s Petit Le Mans, but the #6 Porsche Penske 963 won championships for the team, the manufacturer, and the drivers. Credit: Hoch Zwei/Porsche

Porsche didn’t win this year’s Petit Le Mans, but the #6 Porsche Penske 963 won championships for the team, the manufacturer, and the drivers. Credit: Hoch Zwei/Porsche

The car world has long had a thing about numbers. Engine outputs. Top speeds. Zero-to-60 times. Displacement. But the numbers go beyond bench racing specs. Some cars have numbers for names, and few more memorably than Porsche. Its most famous model shares its appellation with the emergency services here in North America; although the car should accurately be “nine-11,” you call it “nine-one-one.”

Some numbers are less well-known, but perhaps more special to Porsche’s fans, especially those who like racing. 908. 917. 956. 962. 919. But how about 963?

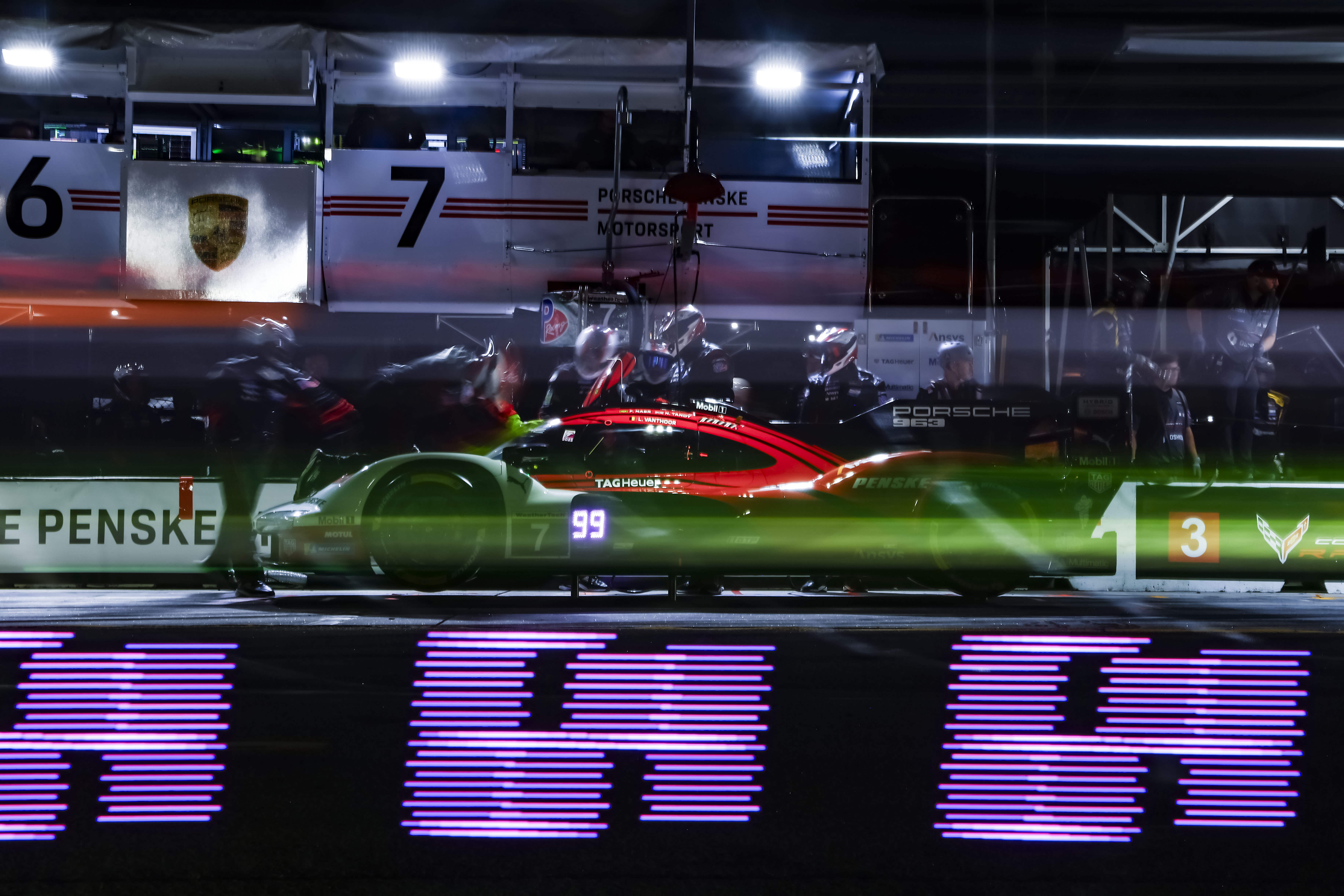

That’s Porsche’s current sports prototype, a 670-hp (500 kW) hybrid that for the last three years has battled against rivals in what is starting to look like, if not a golden era for endurance racing, then at least a very purple patch. And the 963 has done well, racing here in IMSA’s WeatherTech Sportscar Championship and around the globe in the FIA World Endurance Championship.

In just three years since its competition debut at the Rolex 24 at Daytona in 2023, it has won 15 of the 49 races it has entered—most recently the WEC Lone Star Le Mans in Texas last month—and earned series championships in WEC (2023, 2024) and IMSA (2024, 2025), sealing the last of those this past weekend at the Petit Le Mans at Road Atlanta, a 10-hour race that caps IMSA’s season.

49 races, 15 wins. But not Le Mans… Credit: Hoch Zwei/Porsche

But the IMSA championships—for the drivers, the teams, and the Michelin Endurance cup, as well as the manufacturers’ title in GTP—came just days after Porsche announced that its factory team would not enter WEC’s Hypercar category next year, halving the OEM’s prototype race program. And despite all those race wins, victory has eluded the 963 at Le Mans, which has seen a three-year shut-out by Ferrari’s 499P.

Missing the big win?

Porsche pulling out of WEC doesn’t rule out a 963 win at Le Mans next year, as the championship-winning 963 has gotten an invite to the race, and there is still a privateer 963 in the series. But the failure to win the big race has had me wondering whether that keeps the 963 from joining the pantheon of Porsche’s greatest racing cars and whether it needs a Le Mans win to cement its reputation. So I asked Urs Kuratle, director of factory motorsport LMDh at Porsche.

“Le Mans is one of the biggest car races in the world, independent from Porsche and the brands and the names and everything. So not winning this one is a—“bitter pill” is the wrong term, but obviously we would have loved to win this race. But we did not with the 963. We did with previous projects in LMP1h, but not with the 963,” Kuratle told me.

“But still, the 963 program is… a highly successful program because you named it—in the last year, we did not win one win in the championship, we won all of them. Because there’s several—the drivers’, manufacturers’, endurance, all these things—there’s many, many, many championships that the car won and also races. So the answer, basically, is it is a successful program. Not winning Le Mans with Porsche and Penske as well… I’m looking for the right term… it’s a pity,” Kuratle told me.

The #7 Porsche Penske won the Michelin Endurance Cup this year. Credit: Hoch Zwei/Porsche

Was LMDh the right move?

During the heady days of LMP1h, a complicated rulebook sought to create an equivalence of technology between wildly disparate approaches to hybrid race cars that included diesels, mechanical flywheels, and supercapacitors, as well as the more usual gasoline engines and lithium-ion batteries. The cars were technological marvels; unfettered, Porsche’s 919 was almost as fast as an F1 car—and almost as expensive.

These days, costs are more firmly under control, and equivalence of technology has given way to balance of performance to level the playing field. It’s a controversial topic. IMSA and the ACO, which writes the WEC and Le Mans rules, have different approaches to BoP, and the latter has had a perhaps more complicated—or more political—job as it combines cars built to two different rulebooks.

Some, like Ferrari, Peugeot, Toyota, and Aston Martin, build their entire car themselves to the Le Mans Hypercar (LMH) rules, which were written by the organizers of Le Mans and WEC. Others, like Porsche, Acura, Alpine, BMW, Cadillac, and Lamborghini, chose the Le Mans Daytona h (LMDh) rules, written in the US by IMSA. LMDh cars have to start off with one of four approved chassis or spines and must also use the same Bosch hybrid motor and electronics, the same Xtrac transmission, and the same WAE battery, with the rest being provided by the OEM.

Even before the introduction of LMH and LMDh, I wondered whether the LMDh cars would really be given a fair shake at the most important endurance race of the year, considering the organizers of that race wrote an alternative set of technical regulations. In 2025, a Porsche nearly did win, so I’m not sure there is any inherent bias or “not invented here” syndrome, but I asked Kuratle if, in hindsight, Porsche might have gone the “do it all yourself’ route of LMH, as Ferrari did.

“If you would have the chance starting on a white piece of paper again, knowing what you know now, you obviously would do many things different. That, I believe, is the nature of a competitive environment we are in,” he told me.

“We have many things not under our control, which is not a criticism on Bosch or all the standard components, manufacturer, suppliers,” Kuratle said. “It’s not a criticism at all, but it’s just the fact that, if there are certain things we would like to change for the 963, for example, the suppliers, they cannot do it because they have to do the same thing for the others as well, and they may not agree to this.”

“They are complicated cars, yes, this is true. But it’s not by the performance numbers; the LMP1 hybrid systems were way more efficient but also [more] performant than the system here. But the [spec components are] the way [they are] for good reasons, and that makes it more complicated,” he said.

North America is a very important market for Porsche, so we may see the 963 race here for the next few years. Credit: Hoch Zwei/Porsche

What’s next?

While the factory 963s will race in WEC no more after contesting the final round of the series in Bahrain in a few weeks, a continued IMSA effort for 2026 is assured, and there are several 963s in the hands of privateer teams. Meanwhile, discussions are ongoing between IMSA, the ACO, and manufacturers on a unified technical rulebook, probably for 2030.

Porsche is known to be a part of those discussions—the head of Porsche Motorsport spoke to The Race in September about them—but Kuratle wasn’t prepared to discuss the next Porsche racing prototype.

“A brand like Porsche is always thinking about the next project they may do. Obviously, we cannot talk about whatever we don’t know yet,” Kuratle said. But it should probably have something that can feed back into the cars that Porsche sells.

“If you look at the new Porsche turbo models, the concept is slightly different, but that comes very, very close to what the LMP1 hybrid system and concept was. So there’s all these things to go back into the road car side, so the experience is crucial,” he said.

Jonathan is the Automotive Editor at Ars Technica. He has a BSc and PhD in Pharmacology. In 2014 he decided to indulge his lifelong passion for the car by leaving the National Human Genome Research Institute and launching Ars Technica’s automotive coverage. He lives in Washington, DC.